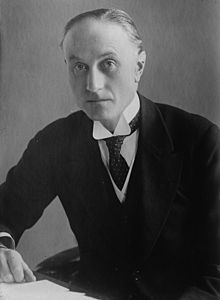

The speech made by Samuel Hoare, the Conservative MP for Chelsea, in the House of Commons on 14 December 1921.

Most Gracious Sovereign, We, Your Majesty’s most dutiful and loyal subjects, the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in Parliament assembled, beg leave to thank Your Majesty for the Most Gracious Speech which Your Majesty has addressed to both Houses of Parliament.

Having taken into consideration the Articles of Agreement presented to us by Your Majesty’s Command, we are ready to confirm and ratify these Articles in order that the same may be established for ever by the mutual consent of the peoples of Great Britain and Ireland, and we offer to Your Majesty our humble congratulations on the near accomplishment of that work of reconciliation to which Your Majesty has so largely contributed.”

It has been the custom of this House for many years past to entrust the duty of moving the Address in reply to the Gracious Speech from the Throne to some Member who has seldom, if ever, addressed it. It is a very good custom, for, with most of us, the less we speak, the more likely the House is to give us a kind hearing and extend to us its indulgence when chiefly we need it. I am afraid that I cannot urge this merit of past silence upon my colleagues. I cannot claim from them the indulgence that is always given to a first offender. I am afraid that I am a hardened criminal, and, as a hardened criminal, I must simply appeal to the mercy of the judge and the jury. They must forget and forgive my past speeches, and grant me a kind hearing for this sole reason: The Session that is opening to-day is unique in the annals of Parliament, and the Address that I am moving differs both in the intensity of feeling it excites, and in the general body of support it commands, from any previous reply that has ever been moved on the Floor of this House.

Let me, at any rate, begin my speech upon a field of universal agreement. Since the House adjourned, two events of outstanding importance have taken place, not only in the annals of the Royal family, but in the history of the British Empire—the landing of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales in India, and the betrothal of Princess Mary to Lord Lascelles. As we mark the continued successes of the Imperial tours of the Prince of Wales—successes in no way impaired by the efforts of despairing agitators—and as we note the general outburst of affection that has greeted the news of Princess Mary’s engagement, we ought to offer our dutiful congratulations to their Majesties, and to assure the King that, if any further proof were needed to justify a hereditary monarchy, the hereditary charm and talent of his son and daughter would make converts of even the most bigoted Republicans.

The Gracious Speech from the Throne concentrates the attention of the House upon one question, and one question alone—”the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland.” “The Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland”—that is the title of the Paper we have in our hands to-day. What a chequered and tragic history, what hopes and fears, what trials, what a long array of great names have gone to make the Treaty that we are to ratify to-day! Strongbow, Strafford, Cromwell, Gladstone, Pitt, Grattan, O’Connell, Parnell, generation after generation—[HON. MEMBERS: “Redmond!” and “Butt!”]—and Redmond—generation after generation, the great figures of our political history have all had their hand in the work that we are asked to approve to-day. There were some of them who believed, in the sincerity of their hearts, that they could settle Ireland by the sword. It has been left to the British Monarchy, in the person of his Majesty the King, to point a better and surer way to settlement. His Majesty’s Gracious Speech at Belfast was the turning point in the crisis. His Majesty’s Speech to-day asks us to gather the fruits that were sown there. Let the Irish people mark the part that the King has played in this settlement. Let them know the value of the British Monarchy. I remember the year 1916, when I was in charge of our military intelligence in Russia, that I met a Finnish agent who came to give me news of Casement’s doings in Germany. He described to me the efforts Casement had made to induce the Irish prisoners in their internment camp near Berlin to join the Irish Brigade of the German Army. How did those Irish Nationalists respond to Casement’s invitation? They drowned his voice by singing “God Save the King.” A race nurtured in these ancient traditions will not be slow to respond to the invitation of His Majesty the King. May we not hope that, with Irish peace established, the Royal influence in Ireland will be still further strengthened by a Royal residence beyond St. George’s Channel?

Let the House throw its mind back to the moment, six months ago, when His Majesty intervened with such telling effect upon the side of peace. Six months ago there was in Ireland a peace that was not a peace and a war that was not a war. Day after day there were events of grim tragedy. Brave men who had withstood the dangers of the Great War were being daily killed and wounded. [An HON. MEMBER: “Murdered!”] A terrible guerilla struggle was proceeding, and the tragedy was all the greater from the fact that although its blood was being shed, and although terror was gripping the land by the throat, the great body of British people in their inner hearts wished to live at peace with their Irish neighbours. There was the Irish tragedy! A terrible war in progress; a great body of British people here wishing to live in peace with their Irish neighbours, yet caught in a vice that seemed to make it almost impossible to escape from the orgy of battle, murder and sudden death.

The real tragedies of history are not the battles between right and wrong, where the issue is clear and the merits of the question undisputed; it is when there is right on both sides that the real tragedies of history are enacted. Such a tragedy was the Irish tragedy. On the one hand the passionate desire of the Irish Nationalists to rebuild the Irish nation; on the other hand the stubborn determination of the forces of the Crown to restore law and order; and behind those two ideals a background set in 800 years of mutual misunderstanding. We might have allowed the tragedy to proceed to its inevitable end. We might have attempted a military solution. No one can deny that had we attempted a military solution the armed forces of the Crown would have carried out the task. The Army and Navy that beat the German Empire would certainly have been victorious. What then? The Irish problem is not a military problem. A military solution could not touch it. If we had killed every Sinn Feiner in Ireland, if we had burned every city in the South and West, if we had laid waste the land, should we have been a day nearer to Irish peace?

We know something of war in this country. There are 5,000,000 of men who went through it three years ago. Does any one of those 5,000,000 men, who weighs the consequences, wish to embark upon a terrible war with his Irish fellow-citizens? In spite of this repugnance, in spite of the general desire for peace, there might have been war. With a quarrel whose roots have sunk so deep and whose poison is spread so wide that it seemed almost impossible to wrench up by the roots the deadly plant. The Prime Minister and his colleagues made the attempt, and we are here to-day to ratify their work. Is it a British surrender this Treaty of Peace that we are discussing to-day? Certainly Mr. de Valera and his “die-hards” in Dublin do not regard it as a British surrender. The British Empire does not surrender to anyone. Our power is so strong, our might so unquestioned, that no one can say that we surrender to anybody. We are so strong that we can make big and generous concessions such as no small and weak country would dare to make. We are making a peace with Ireland, not because we have to make a peace, but because we wish to make a peace. We wish to be the friends, not the enemies, of Ireland. We wish to make our friendship permanent and secure. When the British people make up their minds they do not higgle about details. The British people are a very generous people, and because we are a generous people we say to our former enemies: “Come in and take your part in the British Commonwealth as full partners.” We ask Ireland to take her place as a peer at the Round Table of the Empire’s governors. Not only do we make the invitation. It is an invitation from every one of the great self-governing Dominions of the British Empire.

Not so many years ago we made a similar offer to our former enemies in South Africa. Do we regret the offer we made to our former enemies? Do they regret the agreement they made with their new friends? Ireland, however, is not as the other Dominions. Ireland is a mother country. When Europe was plunged in darkness Irish learning flooded every corner of the Continent. Ireland has her citizens beyond the seas, a company of colonists greater than any possessed by practically every great country except our own. Ireland can bring to the service of the Empire a wealth of history and tradition and foreign influence such as is not possessed by any of the Dominions. More than that, she can bring to the service of the Irish Free State a unique wealth of political experience. No Parliament has passed, but there has been in our Debates here some Irish leader of outstanding.

For a century, from the Irish Benches on this side of the House and on the other, there has arisen a long and unbroken line of great Parliamentary leaders. Henceforth the scene of the triumph of Irish statesmen will be transferred from the sterile deserts of opposition in this House to the fertile field of reconstruction in Ireland. We are taking to-day a long step forward upon the path of peace. We are thankful that we are on the right road. We must not, however, forget the many boulders that have been placed across our steps by past convulsions. The controversy of eight centuries cannot be ended by a Resolution of this House. A battle that has stirred the blood of generations of Englishmen and Irishmen cannot suddenly be stayed by the signature of any political leader.

The Irish Free State has before it a most difficult task—the consolidation of a new, and stable government after centuries of agitation and unrest. Even to-day the first engagement in this struggle is being fought in Dublin. The wreckers of Dublin are attacking the peace. Let us in this House not make more difficult the task of the men of good will. For the first time in modern history Irishmen are to have the full responsibility of governing themselves. Let them show in the service of their own Government the political genius and courage they have shown overseas, and particularly let them show their political courage and genius in their dealings with their fellow Irishmen. If the Treaty is to succeed, the Government of the Irish Free State must at the very outset recognise the solid fact of Irish disunion, and if Ireland is to take the place that is due to it in the world this disunion must be closed and a reconciliation reached between the North and the South. Reconciliation cannot be brought about by Act of Parliament. Reconciliation is the work of the spirit, not of the letter of any statute. The Government of the Irish Free State must give its mind to the great work of reconciliation. Its leaders have made a wise beginning by their offer of fair play to the Southern Unionists. Let this be a good omen for the greater peace between North and South.

As for Ulster, Ulster is free to choose the path that she desires to take. I have great confidence in the political wisdom of Sir James Craig, and I am glad to see that, in his own words, he is

“not dissatisfied at the moment with the outlook.”

I have confidence in the solid sense of the men of the North. They must make their choice. If now or hereafter they find themselves able to join the Irish Free State, how great will be our satisfaction! They will take to the service of a united Ireland their stubborn character, their business talent, their political courage and their burning patriotism. How eagerly we hope that these priceless qualities will not be lost to the new Irish State.

The Conservative party has not always found itself behind the Prime Minister. He would be the first to admit it and the last to resent it. But to-day I venture to say to him from this bench what I believe is in the minds of many other Conservatives. By his resourcefulness, by his energy, by his intuition, he has succeeded where the greatest names in our political history have failed. We offer him our thanks and congratulations for the part that he has played at a critical moment of the Empire’s history. As a Conservative I welcome from the bottom of my heart the hope for reconciliation between English Conservatives and a people that reverences history, tradition and religion.

As a Unionist I am grateful to the Leader of the House for the brave and honest part that he and the Lord Chancellor have played in these difficult negotiations. The union that we have honestly tried to maintain is being transmuted into a union of purer essence. As a party we have played no dishonourable part in Irish affairs. We may have made mistakes, but who in Irish politics has not made mistakes? If we have fought for a lost cause, that cause has not been lost through any fault of our own. We have had our policy, and who shall say that it was not honourably and successfully carried out by men like the Lord President of the Council, like George Wyndham, and like Lord Long? Having done our best I ask my Conservative colleagues to throw their weight into the scale of peace. Is it too much to hope that the Address will be voted without controversy, and that the treaty between England and Ireland will mark, not only the end of a long feud between two great peoples, but the beginning of that new world for which we fought through the long years of the great and terrible War?