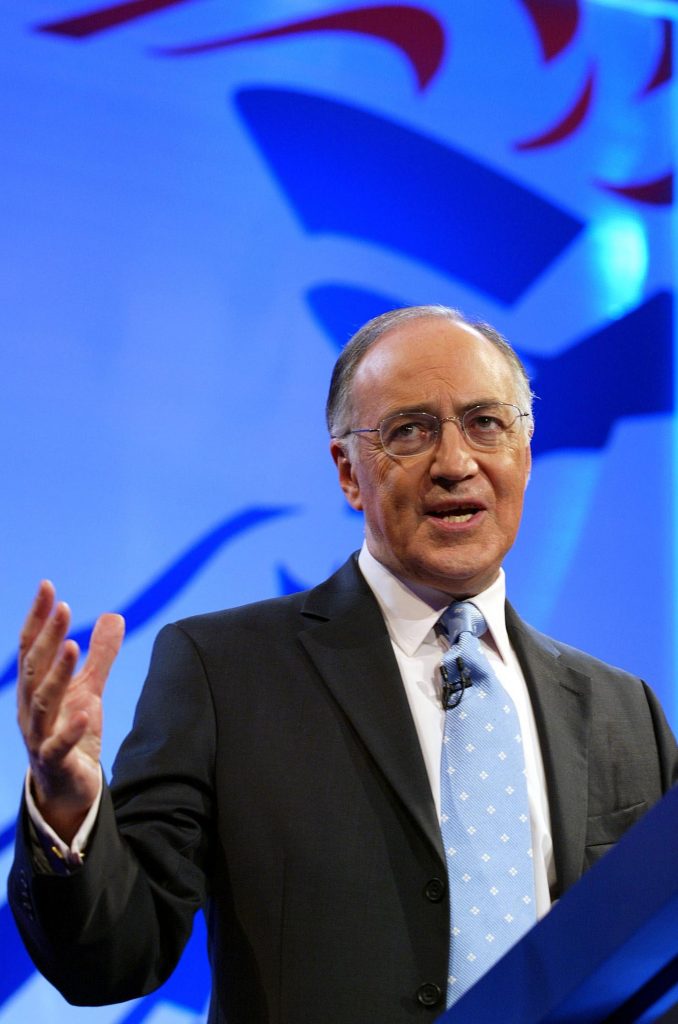

Michael Howard – 2004 Speech to Forum on Trade Justice in the Developing World

The speech made by Michael Howard, the then leader of the Opposition, on 1 March 2004.

“I’m delighted to be here today at the Trade Justice Forum hosted by the Conservative Party.

The subject we are addressing this morning is of absolutely critical importance: because our success or failure will help determine prosperity, peace and democracy right across the globe.

I’m delighted to welcome you all, and in particular Harriet Lamb from the Fairtrade Foundation, Jeremy Lefroy from Equity for Africa, and Bob Geldof.

The Global Challenge

All of us in this room share common objectives. We want to play our part in the alleviation of global poverty. And we want to help developing countries grow and prosper.

With a world facing dangerous political, ethnic and religious divides; and in a world where regional conflicts can have and do have such terrible consequences; the need to narrow the economic divide across the globe becomes ever more compelling.

None of us should ever forget that we share bonds of common humanity with all who share our planet. We should never pretend that we can insulate ourselves from the deprivation of others. We have a duty to help.

Future generations will look back and judge our generation on how hard we tried, and how far we succeeded, in meeting these challenges; by how far we did so in a practical way; and, above all, by how far we did so in a long-term and sustainable way.

Globalisation

At the heart of my remarks today are the benefits which can come from globalisation. These are the benefits which can come in particular to poorer countries as companies look across the world at new markets and new opportunities. They are the benefits which come from the ease, speed and cheapness of electronic communication and the internet. And they are the benefits which come as countries and organisations agree to conform to international standards, rules and practices.

There are numerous examples of countries that have prospered by abandoning inward-looking policies and adopting outward-looking policies.

The most recent dramatic examples are India and China, which have averaged 4% and 8% real per capita growth respectively over the past decade or so. As a result, the World Bank estimates that the proportion of people living on less than $1 per day in China has fallen from 33% of the population in 1990 to 16% in 2000, and in India from 42% in 1994/5 to 35% in 2001.

This is a huge and almost certainly unprecedented reduction in poverty affecting the lives of millions of people. We should celebrate it.

Free Markets

Free markets deliver the greatest benefit. I passionately believe that countries that adopt the market economy are the ones that will ultimately prosper.

Look at the most successful economies across the world. They are living proof that free markets are the most effective means of wealth creation and wealth distribution. And no surprise that these are the countries where people enjoy high living standards, not just in personal disposable income but also in education and healthcare.

Free markets and free trade generate the wealth that helps lift people out of poverty.

Look at countries such as Mexico, Vietnam and Uganda. Over the 1980s and 1990s these countries doubled the ratio of their exports to GDP, and in the 1990s their growth rates averaged 5%. By contrast countries such as Myanmar, Ukraine and Pakistan saw the ratio of their exports to GDP fall during the 1980s and 1990s, and GDP per capita fell on average by 1% a year in the 1990s (D Dollar & A Kraay, Globalisation, Growth and Poverty, World Bank 2002).

Opening Up Markets

But for this to happen, the rich countries must open up their markets. That is an essential part of the long-term solution.

It is appalling that the West should close its markets to so many of the world’s poor. It is even worse that it should target its tariffs primarily to exclude agricultural products.

And the result? For every dollar that western countries give to poor countries, those countries lose two dollars through barriers to their exports to the developed world. So, for the developing countries, it’s one step forward and two steps back. This is hardly the right way to help our fellow human beings – more than a billion – who have to struggle to survive on less than a dollar a day.[1]

Instead, we need to work together to open our markets to the developing world. It is a terrible indictment of our progress in this area that the poorest countries’ share of world trade has dropped by almost a half in the last twenty years.[2] But is it any wonder when those countries which advocate free trade don’t always live up to their rhetoric.

For example, in 2001, the United States imposed tariffs to protect its domestic steel industry, which have only recently been removed. In 2002, the US and Japan spent $90 billion and $56 billion respectively supporting their domestic agriculture.[3] Indeed subsidies to farmers in rich countries total $300 billion a year, more than the combined income of the whole of sub-Saharan Africa[4]. Cotton is crucial to certain West African countries – Benin, Burkino Faso, Chad, Mali and Togo – and almost the only commodity they can export. But the US and China provide huge subsidies to their domestic producers – subsidies which stimulate artificial production, reduce world prices and lower the incomes of small cotton producers in these countries.

The richer countries should act in accordance with what they know to be true: free trade spreads prosperity. Protectionism does not.

Democracy and the rule of law in the developing world

We should also encourage the development of property rights, the rule of law and democracy. These are not only of direct benefit to the citizens of those countries. Crucially, they create the stability essential for more trade and more investment – a virtuous circle.

As the economist Hernando de Soto so vividly puts it:

“Imagine a country where the law that governs property rights is so deficient that nobody can easily identify who owns what, addresses cannot be systematically verified, and people cannot be made to pay their debts. Consider not being able to use your own house or business to guarantee credit. Imagine a property system where you can’t divide your ownership in a business into shares that investors can buy, or where descriptions of assets are not standardized. Welcome to life in the developing world, home to five-sixths of the world’s population.”[5]

President Clinton referred to de Soto’s work a few years ago in his Dimbleby lecture, when he stressed the importance of the rule of law and said: “Poor people in the world already have five trillion dollars in assets in their homes and businesses but they’re worthless to them except to live in and use, because they can’t be collateral for loans. Why? Because they’re outside the legal systems in their country”.[6]

Good governance, buttressed by the rule of law, provide the order and stability essential if others are to have the confidence to trade with and invest in these countries. The lower risk, the greater the confidence. The greater the confidence, the greater the trade and investment flows. That is the way to create prosperity and spread prosperity.

An Advocacy Fund

Part of the mechanics of the process of actually getting something done to help the developing world is the regular round of world trade negotiations – although the collapse of the Cancun talks were a disaster for the developing world.

I have for some time now been calling for the establishment of an Advocacy Fund for developing nations. With the World Trade Organisation, we have a rules-based system governing world trade in which trade disputes are not decided simply on the basis of which countries have the biggest muscle power. But, so far, poor countries have not been able to take full advantage of this system because they lack the necessary expertise.

A practical solution to this problem would be for the rich countries of the world to set up and pay for an advocacy fund which would pay for the necessary expertise to help poor countries realise the enormous potential of the new trade regime.

An Advocacy Fund would help solve the well-known problem, namely the ability of the developed world to out-gun its opponents in trade talks with an army of lawyers, economists and accountants. And an Advocacy Fund would help to provide much more of a level-playing field.

Overseas Aid

But although trade is of paramount importance, aid is key too. As is well-known I supported the announcement in November 2002 by Gordon Brown of the establishment of the International Finance Facility. The establishment of the IFF explicitly recognised the changed context in which aid policy is developing, namely that the reduction of poverty lies ultimately, as I have said, on the growth of free trade and the reduction of protectionism.

The joint paper by the Treasury and the Department for International Development on the IFF in January 2003 makes that clear: aid, it says, “must be an investment for success based on clear, country-owned poverty reduction strategies, building on the foundations of stability, trade and investment”. In other words, aid is a two-way process, where countries that are putting in place institutions and mechanisms to provide long-term internal stability will be the ones that benefit most from aid.

I believe that Britain has one of the most effective overseas aid and development programmes in the world, where almost all of the aid reaches the people it is intended to help and is used effectively. It has been made more effective by the decision of the UK government in 2001 to untie aid from export promotion. The World Bank has clearly shown that tied aid is 25% less effective than untied aid, in that tied aid restricts the freedom of choice of recipient countries, and more countries should follow the UK’s example.

Make no mistake, a future Conservative government would be committed to Britain’s overseas aid programme. Well-directed, bilateral government aid has to remain a significant component of our aid strategy.

Making more effective use of money currently spent on a multilateral basis will also be important.

As someone who is genuinely concerned with the need to give British taxpayers value for money, and to alleviate global poverty, I find very persuasive the case for increasing national control over overseas aid and development, particularly that currently managed by the European Union.

We shall also seek ways of encouraging the increased involvement of NGOs, and of charitable and private giving, in the setting and implementing aid policies. As Brian Griffiths notes in his recent pamphlet on global poverty, the private and voluntary sectors have hitherto been marginal in the way in which aid finance is spent, yet in certain countries they have played a vital role in establishing schools and hospitals. One of the key criticisms of foreign aid is that it is used to strengthen the power of corrupt governments. One of the best ways round this problem is to strengthen the role of NGOs and the private and voluntary sectors in the delivery of aid.

Having said that, I also agree with Brian Griffiths that the culture of the aid community is still too closed. The work and audits of governments and development banks should be published and open to scrutiny.

It is also important that we target aid at the countries that need it most. Less than half of the EU’s aid budget goes to poor countries. Much of it, for political reasons, goes to “middle income” countries, who should, in my view, be a lower priority than the least developed countries. When we look at our own aid policy, it is vital that we also target aid at poor countries.

Conclusion

I want to conclude my remarks this morning by thanking all the organisations represented here for the tremendous work that you do by maintaining the pressure and momentum for change. In turn, I want to assure you that we in the Conservative Party will play our part in working for reform – in removing tariff barriers; in encouraging democracy, good governance and the rule of law; and in effective management of overseas aid budgets.

The challenge is immense. But the rewards would also be immense, for our world and for the world of future generations. It is a cause in which I passionately believe and I salute you for your efforts in trying to turn all our concerns into real and significant progress.