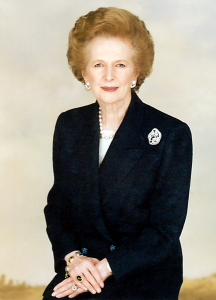

Below is the text of the statement made in the House of Lords by Baroness Margaret Thatcher on 6 July 1999.

My Lords, my noble friend Lord Lamont has done the House a service by initiating this short debate on a matter of great importance to Britain’s reputation, to Chile’s stability and to the orderly conduct of international relations. I shall try to deal with each of those matters while seeking to avoid remarks about the case itself.

Britain’s reputation should be of vital importance to the government of the day. Our reputation sustains our interests. The Pinochet case has sullied that reputation. Senator Pinochet came here last September as a long-standing friend of Britain. Though I shall not go into the details, I can say that without President Pinochet’s considerable practical help in 1982, many more of our servicemen would have lost their lives in the South Atlantic. The country thus owes him a great debt.

After leaving power he was accordingly received here as an honoured guest on a number of occasions. Similarly, on 22nd September last year, when he entered Britain on a diplomatic passport charged with a special mission by the current Chilean President, he was accorded all the privileges of an ambassador, including the protection of the Metropolitan Police Diplomatic Protection Squad.

However, some weeks later the general was arrested in hospital at dead of night, when under heavy sedation following a serious back operation. There is a widespread suspicion that there had been collusion between the British and Spanish authorities prior to the arrest, when the Chileans were not given the warning they might have expected about the imminent risk. That inhumane arrest was in any case made on the basis of an unlawful warrant. Senator Pinochet was then held for six days illegally under that warrant. Those circumstances left Britain’s reputation for loyalty and fair dealing in tatters.

Secondly, I want to speak about the situation in Chile—this country’s oldest and truest friend in Latin America. The great majority of Chileans, even the political opponents of Senator Pinochet, feel wounded at the way we and the Spanish have treated them. They are right to do so. Until the Senator’s arrest last October, Chile had achieved three remarkable successes, all of them in large measure due to former President Pinochet.

First, it had seen the total defeat of communism at a time when that ideology was advancing throughout the hemisphere. As Eduardo Frei, the former Christian Democrat president of Chile put it: “The military saved Chile”. Secondly, Chile has seen the establishment of a thriving, free-enterprise economy which has transformed living standards and made Chile into a model for Latin America. Thirdly, Chile is also remarkable because President Pinochet established a constitution for a return to democracy, held a plebiscite to decide whether or not he should remain in power, lost the vote (though gaining 44 per cent support), respected the result and handed over power to a democratically-elected successor.

Chile thus enjoyed prosperity, democracy and reconciliation—until we and the Spanish arrogantly chose to interfere in her affairs. So far, the Chileans have behaved with great restraint. But we should not assume that this will continue, particularly if Senator Pinochet, who is not now in the best of health, were to die in Britain or is taken to Spain. Anything that happens then will be the direct responsibility of this Government and, in particular, of the Home Secretary.

My final point concerns the implications of the Pinochet case for the conduct of international relations, which are essentially based on trust between nation states. This trust has now been shattered by the prospect of the courts in one country seeking the extradition of former heads of government from a second country for offences allegedly committed in a third country.

Senator Pinochet is, of course, being victimised because the organised international Left are bent on revenge. But on his fate depends much else besides. Henceforth, all former heads of government are potentially at risk; those still in government will be inhibited from taking the right action in a crisis, because they may later appear before a foreign court to answer for it—

Lord Carter My Lords, perhaps the noble Baroness would be kind enough to give way.

Baroness Thatcher My Lords, I am nearly at the end of my speech.

Lord Carter My Lords, I should just like to remind the noble Baroness that this is a timed debate and the limit for each speaker is four minutes. The noble Baroness is now in her seventh minute. I wonder whether she could now bring her remarks to a close.

Baroness Thatcher My Lords, I am very close to the end and I very rarely take up the time of this House. It will now take me longer because the noble Lord interrupted me in the middle of a sentence.

Henceforth, all former heads of government are potentially at risk; those still in government will be inhibited from taking the right action in a crisis, because they may later appear before a foreign court to answer for it and—this is where I was when I was interrupted—in a final ironic twist, those who do wield absolute power in their countries are highly unlikely now to relinquish it for fear of ending their days in a Spanish prison. This is a Pandora’s box which has been opened—and unless Senator Pinochet returns safely to Chile, there will be no hope of closing it.