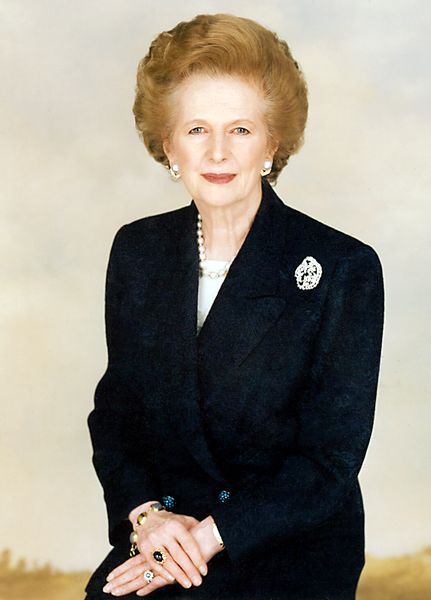

Below is the text of the speech made by Margaret Thatcher, the then Leader of the Opposition, in the House of Commons on 1 November 1978.

It is the privilege of the Leader of the Opposition to congratulate those who move and second this motion. I do so very warmly on this occasion, even though, as the right hon. Member for Anglesey (Mr. Hughes) hinted, it is rather unexpected. I know that the whole House will applaud the choice of the right hon. Member for Anglesey to move the motion. I use the traditional formula of “the right hon. Gentleman” but it might have been more appropriate to refer to him as a friend of the House. Certainly, he has many friends on both sides of the House. That does not mean to say that people who are friendly with those on the opposite Benches are any less loyal to their own party.

The right hon. Gentleman will leave this House in the same spirit of good will in which he finished his work in two senior posts in Government. But, as he asked, when will he leave? I gathered from the right hon. Gentleman’s comments that he was one of those hon. Members who were prominent in saying their goodbyes in July. What he has just said shows that not even the chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party can foretell the future.

The right hon. Gentleman is a Welsh speaker. I understand that he claims that Welsh is the language of heaven. I hope not, because that would mean that many of us would not see much of him in the future.

I should like to make one further comment about the right hon. Gentleman. In recent years, as chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party, he has worked closely with my right hon. Friend the Member for Taunton (Mr. du Cann) in the interests of Back Benchers. That work will not be forgotten. The right hon. Gentleman has been a Member of Parliament for 25 years. I am sure that he will understand now if I wish him an early enjoyment of the holiday that had to be postponed from October.

The hon. Member for Thornaby (Mr. Wrigglesworth) has been in the House for only a few years by comparison. He always makes reasoned and measured contributions. I understand that the hon. Member’s Whips do not rank him amongst their rebels, but I should have no grumble about that. He made an interesting speech. He drew attention to the unemployment problems in Teesside. I hope that he will continue to impress upon his leader and on his constituents that after four years of Labour Government twice as many people are out of work as when the Conservatives left office.

There have been times in the last few months when many of us felt that it was as if all our problems were being discussed in terms of x per cent. It was as if some mysterious percentage would solve all the sophisticated problems of the British economy and all the sophisticated problems of industry and commerce.

Pay policies, of course, are extremely important, but so, too, are policies for higher production, policies for good profits and policies for new enterprises. It seems to me that we have concentrated so much on continual restraint—I accept that we still need to have restraint in a number of directions—that we have paid far too little attention to incentive and enterprise. We have been so busy analysing the reasons for the comparative decline of Britain that we have forgotten to analyse the recipes for success of some of our Continental friends.

Job for job, their production per person is higher. Job for job, they have a higher standard of living. Job for job, they pay less tax, they save more and they can do more for their children. Because they have concentrated not only on pay policy but on output policy, they have produced enough to provide for differentials, so they do not have the problem of wage explosion that we have. They have produced enough to pay their public sector well. They have produced enough output to provide better pensions, better provisions for the disabled, and more money to be spent on health.

During his party conference the Prime Minister spoke about poverty. He said that where there was poverty there would always be a need for a Labour Government. That is because where there is a Labour Government there will always be poverty.

When I was first a junior Minister I was attached to the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance. I was questioned regularly by my right hon. and hon. Friends. They said that it was a disgrace and a great reflection on the affluent society that about 2½ million people were on national assistance. Today, after four years of Labour Government, is not it a disgrace and a reflection on them that there are now 5 million people who have to have recourse to social security? That number has increased by 1 million during the last four years. Whenever there is a Labour Government there will be poverty, because Labour concentrates far too little on wealth creation and far too much or redistributing what there is.

The Gracious Speech, Mr. Chairman—[Interruption.] My apologies, Mr. Speaker. Perhaps we have been kept away from this House for too long, bearing in mind that it is the forum of the nation. The Gracious Speech contains a number of matters of a constitutional nature. It refers to the referendums for the proposed Scottish and Welsh Assemblies. My right hon. Friend the Member for Cambridgeshire (Mr. Pym) said that had things turned out a little differently we would have held the referendums on 22nd March, and that had the necessary number of votes upon which Parliament had decided been reached we would have recommended that the Assemblies go ahead. At the moment, however, I cannot conceal that many of us feel that this is the last Parliament in which we shall all sit together representing all parts of the United Kingdom as Members with equal powers, equal duties and on equal terms. If the Assemblies go ahead, there will be serious difficulties in the United Kingdom Parliament. We may look back on the last year of legislation as one which gave us grievous difficulties and did great harm to Parliament at Westminster.

The Bill to increase the number of parliamentary representatives for Ulster will command great support from us. There will be no difficulty from this side of the House about securing an easy passage for that Bill. I rather had the impression, when announcements were made about it, that there would be considerable difficulties from the Labour side but none from us.

I have to put one proposition to the Prime Minister. When he said that he would be asking Mr. Speaker to have a Speaker’s Conference about increasing the number of Members representing Ulster, I pointed out that under his authority now there is one great part of the United Kingdom which is badly under-represented, and that is England.

Whether that situation exists wittingly or unwittingly on the Prime Minister’s part—I suspect that he has political and parliamentary reasons for keeping England under-represented—I hope that in due course the position will be changed.

It was obvious from one or two sounds that came from various parts of the House that I am expected to say quite a bit about what the right hon. Member for Anglesey called one of the central parts of the Gracious Speech—that which refers to inflation and unemployment. Of course we share with the Government the desire to achieve the same ends on this matter. That is not enough. We accept that inflation must be reduced. As the Prime Minister is often pointing out, inflation is now below what it was when we left office, but I point out to him in return that during our time in office we got inflation down to 5·8 per cent.—an objective that he has not yet achieved.

We share the same objective of reducing inflation as a priority. Of course, we share the same objective that unemployment must be reduced. After all, it was this Government who put both of them up. Of course we share the objective that there must be a stable currency, because without it there can be no confidence in investment or in expansion, and we shall not get the growth that we need.

I even had the impression, from a number of things that the right hon. Member for Anglesey said, that we not only shared the same ends but agreed on a large number of the means. He referred to money supply policies. Whenever money supply or monetarism was mentioned in this House the Chancellor of the Exchequer would accuse us of monetarism, of “Josephitism”. At the next moment, the Chancellor would say that he was far better at holding the money supply than we were. I am glad that the Chancellor says that he has been wholly and utterly converted to the necessity of holding the money supply very firmly. We agree with him wholeheartedly, for reasons that he knows. That is the only final way in which inflation can be held and reduced. He knows it and we know it.

The Chancellor got inflation up to a far worse level than we ever did. He boasted at the last General Election that he had got it down to 8·4 per cent. Of course, he had not. We accept that money supply must be held very firmly. We noticed that in his Mansion House speech the Chancellor said that he had given monetary policy the importance it deserved.

We shall never get inflation down unless we get the money supply right. There is no inflation in a barter society. It is only when money is put into it that the phenomenon of inflation arises. If too much money is put in, obviously there will be inflation.

It was a long time before the Chancellor was converted to the total means of getting down inflation. The IMF insisted that he had money supply targets, but it also insisted that he cut spending under the profligate policies that he had pursued. It also insisted that he cut borrowing—a great change from the policies that he had previously pursued, although he has not taken enough of that advice to heart. He also knows that one of the reasons—in addition to money supply, spending and borrowing—for inflation falling is that North Sea oil has permitted a rise in the exchange rate. But for that he could hardly have reduced inflation last year to 8 per cent.

He said—I believe that he and the Prime Minister got their arithmetic wrong—that with wage increases of 14 per cent. or 15 per cent. there would be inflation of 14 per cent. or 15 per cent. He was wrong. Last year average earnings increased by 14 or 15 per cent., but the rate of inflation fell to 8 per cent. That happened because of the factors that I have enumerated. Inflation will never be reduced—it is as well for the Prime Minister and the Chancellor to be clear about it—unless these factors are right, because it is they that hold inflation or reduce it.

Of course, in fixing the money supply it is necessary to take a view about how much growth there will be in the economy, and that view has to be realistic. In 1976 the Chancellor sent three estimates across to NEDC. The NEDC chose the highest because it could not bear the consequences of public expenditure if it chose the lowest. That is not taking a proper view of the rate of growth. That view must be realistic in all the circumstances. We said in “The Right Approach to the Economy” that it should be proclaimed, discussed and explained. Everyone must understand that the only improvement that can be made in wages is that which comes from real increases in output, which is why other countries have done so much better than we have.

We have to take a view of the growth rate, and in taking that view we have to take a view of the element in it represented by wage costs and consider how much that will be. When the budgets for each and every Department are done, one has to take a view of the estimate for the increase in salaries and wages. None of this is in dispute. The dispute arises, I think, over whether that view is an average or whether it becomes a norm. I must say very strongly indeed that in our view that figure is an average and can never be a norm except in conditions of emergency.

All Governments from time to time have had incomes policies, whether it be the Labour Government from 1965 to 1970, the Conservatives from 1970 to 1974 or the present Government. We all know that in time they break. We all know that they break, and then we have to make preparations to get back to what I would call responsible collective bargaining.

I said a moment ago that there was a good deal of agreement not only on ends but on means. The Chancellor of the Exchequer wrote a letter to my right hon. Friend the Member for Lowestoft (Mr. Prior) just about phase 3. What did he say about phase 3? The House will remember that phase 3 started as a 6 per cent. wage settlement, finished up as a 10 per cent. settlement, and then finished up as a 15 per cent. or 16 per cent. increase in average earnings. This is what the Chancellor said:

“The task in the next 12 months is to complete the transition to responsible collective bargaining”—

hon. Members will notice that that is the phrase that my right hon. Friends and I have been using—

“The task…is to complete the transition to responsible collective bargaining from two years of rigid pay restraint.”

The Chancellor went on to say:

“most settlements will have to be well within single figures. But it is common ground between us”—

his phrase—

“that we cannot specify the level of particular settlements in this transitional period.”

There is a very great measure of agreement on means as well as ends.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer knew that he could not go on holding a rigid incomes policy, and I really doubt whether any Government wants to do that. It does not seem to be at all realistic to have x per cent. to solve all the many and complicated problems in many different circumstances in industry.

Incomes policies of a rigid kind do not fail because they are unpopular. They are, of course, very popular. Looking at all the opinion polls, I naturally have a particular interest in those taken around February 1974. We could have done with more support from the Prime Minister at that time. [HON. MEMBERS: “Oh”.] What was the Prime Minister doing at that time but stumping around Aberdare saying,

“We all know the lie about the 16 per cent. the miners are supposed to be getting under a special arrangement of the phase 3 legislation. I will say to Mr. Heath that if he is returned on February 28th, unless he has more money to put on the table, he has a bigger struggle on his hands than he has ever imagined. Mr. Heath is arguing that he is fighting inflation. That is utter drivel.”

That was the kind of support that the right hon. Gentleman was prepared to give to what at that time was a statutory incomes policy.

That, too, broke, but it broke not because it was unpopular with the people. It broke because after one has had a certain number of rigid phases, one must in fact return to responsible collective bargaining.

As my noble Friend Lord Boyd-Carpenter said in a very vivid letter to The Times the other day, the pay policy is like a battleship designed by the German Emperor for his naval chief of staff. All the guns, all the ammunition, all the equipment required are there. It is just that it will not float. We have reached the stage now when, after three phases, a rigid incomes policy just will not float. It just will not hold. There is no point in arguing about it as if it will float; it will not float. We get all sorts of fudging deals, all sorts of “phoney” productivity deals. What my hon. Friend the Member for Oswestry (Mr. Biffen) says about productivity deals is very good. He says that they are the elastic device whereby the policy can be stretched to meet the ultimate truth of the market place. That is exactly what is happening. So, rigid percentage incomes policies at this stage—no: they cannot and they will not hold.

However, that does not mean that one can abandon all constraint. [HON. MEMBERS: “Oh”.] Of course, it does not. The constraint on one’s money supply is there, and that is the only thing that will ultimately hold inflation. That is why the Chancellor said so in his speech at the Mansion House the other day. To deny that is completely to misunderstand the nature of inflation.

If in fact one has more and bigger and bigger wage increases—and this is why one has to do so much propaganda about it; and the right hon. Gentleman knows and I know—people will price themselves out of the market, output will go down and unemployment will go up. That is the purpose of urging more and more restraint upon those who are doing the bargaining.

I believe that the Government’s rigid 5 per cent. policy will fail. That is not because I believe that people should demand more than 5 per cent. for nothing. Five per cent. for nothing as a starting point seems to me an ultimate recipe for inflation, if one then moves the money supply up to accommodate it. However, I must just point out that the official guidance to civil servants on the 5 per cent. pay policy is one of the most pernickety bits of bureaucracy that I have ever seen and one that I believe would bring productive and creative industry to a dead stop. Let us just look at the first paragraph:

“Any case which gives rise to serious doubt should therefore be referred to the Department of Employment, who will arrange for it to be brought to the official Committee and Ministers as appropriate.”

So we shall get every single case in which there is any doubt going up to some central body. We shall have companies—some of them very successful—which are producing exports and have got the Queen’s Award for Export having two things happening. First they have got the Price Commission in, causing all kinds of trouble—although very few people there know what efficiency is in particular industries. Then, just when they have had trouble and could make their own decisions on the spot with their own shop stewards and trade unions, the matter has to be referred right up to some central body.

That is no way to run industry. It is no way to raise production and to enable us to compete with other countries.

Another paragraph—this was never published except by The Times, says “Use only if pressed.” That acknowledges that under Socialism, under this Labour Government, many people, in order to get more out of the rewards from work, have had to go to benefits in kind. So there is a paragraph which assesses whether the benefit in kind this year is more than 5 per cent. more than it was last year, and so on.

One cannot now run a rigid pay policy like that. But what I believe is happening is that the Prime Minister is perfectly well aware of that. He knows it. But the battle now and the thing that people are really worried about as we go towards more “responsible”—in the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s language—collective bargaining is whether the trade unions will be responsible. That is the question that people are asking. The question about which they are fearful is whether trade unions have so much power that they will abuse that power. That, whether or not one likes it, is a question that is exercising the minds of our people, and it is a question to which the Prime Minister should be addressing himself—not just taking it at a rigid incomes policy level.

But I underestimate the Prime Minister. He did address himself to it about nine years ago, when other members of his party were addressing themselves to it and published “In Place of Strife”. The Prime Minister was a person who not only addressed his mind to the problem of trade union power but saw that that White Paper was consigned to the waste paper basket. Not only has he insisted that all of their powers remained exactly as they were; he has increased them during his term of office. He did not resist any change. He increased the powers of trade unions. What happened during phases 1, 2 and 3 was not that those agreements were obtained voluntarily—not in any way. We are dealing with negotiators who are far too skilled for that. They were obtained at a price. The benefit given by the trade unions, in terms of co-operation, was a temporary one. What they got in return were permanent or semi-permanent benefits. One of those prices was a great increase in public expenditure, which landed the Chancellor in difficulty with the IMF.

Another price was giant strides towards Socialism, with increased nationalisation, which the Government have put permanently on the statute book. The Prime Minister and the right hon. Gentleman the Leader of the House were instrumental in obtaining those. The third price was a great increase in the power of trade unions, which made the trade unions the most powerful the whole world over, including the closed shop. Therefore, the Prime Minister is not the person to complain about trade union power or to pose as the person who can in fact stand as a bulwark against it.

There are two things about power. First, there is its existence in law—we are not arguing about that, it is there—and, secondly, there is the use of the power. I believe that things have changed very much since February 1974. I do not believe that one ever fights the same battles on the same ground again, so let us turn, as we ought, to look at the use of that power.

More than 11 million people are members of trade unions. There are not 11 million irresponsible people in this country who will put their own future and that of their families in jeopardy. If one believes that there are, one can have no faith at all in the future of democracy. There are not 11 million irresponsible people—or 10 million, or 9 million. There might be a few who wish to use the power of the system to bring down the whole of the free enterprise world and substitute another central system for it.

The question then becomes: ought one, in the Gracious, Speech, to be looking at the structure of trade unions, at any structure which enables a few people to take power, pose as though they represent a large number—which they do not—and effectively make it difficult for the great majority to make their views and voices heard? That is why we have given attention to a postal ballot paid for by the Government. But there is nothing about that in this Gracious Speech. There is nothing, when we are going into a new phase of incomes policy, to assist the ordinary member of a trade union to make his or her voice heard without intimidation, without having to face some of the scenes that some of us saw on television at the Vauxhall meeting.

The other point to which the Prime Minister ought to be addressing his attention is how to stop circumstances of that kind, and he ought to bring to bear all the powers of the land against—

Mr. Heffer rose—

Mrs. Thatcher

May I just finish this sentence?

Mr. Russell Kerr (Feltham and Isleworth)

He is a member of a union.

Mrs. Thatcher

So was I. I was a member of the Association of Scientific Workers when I was an industrial chemist, and I sometimes said to Clive Jenkins “If things had turned out a bit differently you would be in my job and I would be in yours”.

As I was saying, we ought to bring to bear all the powers of the land to check and stop the intimidation and to enable people to make their views freely and easily felt, as befits a democracy.

Mr. Heffer

I am following the right hon. Lady’s speech very carefully. Is she suggesting that we should get back to something like the proposal made by her right hon. Friend the Member for Sid-cup (Mr. Heath) in the Industrial Relations Act 1971? Is she suggesting that there should be ballots? Should she not take into consideration the ballot held by the National Union of Railwaymen? Should she not take into consideration the ballot of the National Union of Mineworkers, and the types of ballot that could continue a strike when the rank and file are in favour of settling a strike? Has she not learned the lessons of the disastrous days when her right hon. Friend was Prime Minister?

Mrs. Thatcher

The answer to the first half of the hon. Gentleman’s question is “No”, and as the answer to the first half is “No” the second half, with respect, does not follow. No, I was not proposing that. Our proposal is for Governments to pay for postal ballots at the instance of the members of the union. The hon. Gentleman knows, and I know, that in a democratic system one has to make it easy for people to make their views known. It takes a tremendous amount of courage to go to those meetings and stick up one’s hand. The hon. Gentleman knows that better than I do.

I am suggesting that if a large number of people want a postal ballot—want it; it is not compulsory—the Government should pay for it. I am saying this because I believe that the problem to which we ought to address our minds is how to let the 11 million responsible people make their views felt and known. The trouble is that Labour Members will not even address their minds to that issue, let alone take it up with the trade unions themselves. But I believe that the majority of trade union members are responsible, and that the majority of trade union leaders are responsible. If one does not believe that, there is no future for democracy.

The Gracious Speech also says something about Rhodesia. As we heard from you earlier, Mr. Speaker, we shall be having two days’ debate on the general problem of Rhodesia—as I understand it. This whole question of Rhodesia is very important in the minds of many British people at the present time, particularly since arms have been sent to Zambia and since the Prime Minister’s visit to President Kaunda. I think that this afternoon the Prime Minister ought to answer many questions before we go on to that debate.

May I ask the Prime Minister a few questions? What safeguards have the Government insisted upon when sending British arms in British planes to Zambia? Are these arms to be used to defend the guerrilla camps from which, increasingly, Nkomo is attacking the people of Rhodesia? Is that what the Foreign Secretary means when he talks of evenhandedness and asks Mr. Smith and the other members of the transitional Government to attend an all-party conference? If one helps to protect one side, can one blame the other for doubting one’s impartiality?

What else did the Prime Minister agree to do at that meeting in Kano? What else did he agree to do at that curious secret meeting and visit, from which journalists were meticulously excluded? Has he agreed to the use of British troops? If so, the British people will be outraged. What other secret agreements has the Prime Minister reached? We have a right to know, because many of us cannot see the guerrilla leaders coming to the conference table until they believe that they will get more that way than they will by fighting and by the use of the bullet. We shall, Mr. Speaker, be tabling for your consideration an amendment against the Government’s handling of the whole Rhodesian matter.

This is the last Gracious Speech of this Parliament, and when the Parliament is at an end—I accept that we do not know when that will be, and I accept that I cannot bring it about in any way; it is the Prime Minister’s choice, and if he wishes to go on to the bitter end, so be it—and the election comes, I believe that it will be fought on very deep and fundamental issues, and I believe that we have to bring these to the attention of the people.

The election will be fought on the question whether people want to give more power to Governments or want more power to make their own decisions over their lives. I understand and know that many people joined the Labour Party to protect the little man against the big battalions, but now Labour has become the party of the big battalions and big bureaucracy. Another Labour Government will put infinitely more power into the hands of Government, because so many of them believe in collective decision and make far too many decisions political and leave far too few to be taken by people on matters affecting their own lives in their own way.

The election will be fought on the role of Government in economic matters—whether people want more and more nationalisation. This Gracious Speech is very different from the one that Labour puts forward when it has a majority. More nationalisation was approved at the Labour Party conference—North Sea oil, land, the construction industry, the insurance industry and pensions. The election will be fought on the question whether people want to go our way and have more choice, which can only be through a free enterprise system and through more and more competition.

The election will be fought on the question whether people want more and more of their wages spent by the Government through increased tax on the pay packet, or whether they come our way and have reduced taxes on their pay packet, leaving them to spend more of their own money in their own way. Tax cuts are a Tory policy. It would perhaps be as well to remember that the tax cuts coming in November were driven through against the wish of this Government.

The election will be fought on the question of whether people take the view of law and order which they saw demonstrated at the Labour Party conference, which was described graphically in The Guardian and which we all saw on television, or whether they wish to take our view; whether people want to depend on the State for everything from the cradle to the grave, or whether they wish to acquire more personal capital for self-reliance. They will never do it under a Labour Government; a Labour Government will take it away from them. That is one of the great differences in this country—one cannot acquire capital out of earnings merely by savings. It is our policy to leave people with enough of their own money to be able to acquire personal capital, to have more self-reliance and self-help, to have more self-reliance and resources, to be able to do more for their own children. What is so wrong about that?

The result of the election will depend above all on the kind of priority people wish to give to the defence of the Western way of life—whether they believe in the low priority accorded by this Government or believe, as we do, that our first duty to freedom is to defend our own.

This Gracious Speech is an attempt to try to prove that the Labour Party is what it is not. It is an attempt to prove that it is more moderate than it is, and to keep the Left wing of the party very quiet indeed. [Interruption.] I must say, the prospect of keeping them quiet is extremely remote.

What people want now is a Conservative Government, with Conservative policies and a Conservative way of life. They will get that not from a Labour Government posing that way but only from a Conservative Government with true Conservative policies. We look forward to the next Gracious Speech.