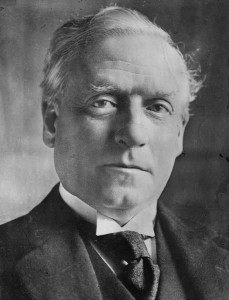

Below is the text of the speech made by Herbert Asquith, the then Prime Minister, in the House of Commons on 27 April 1908.

Mr. Speaker, many of us, Sir, have come here fresh from the service in Westminster Abbey, where, amidst the monuments and memories of great men, the nation took its last farewell of all that was mortal in our late Prime Minister.

Sir, there is not a man whom I am addressing now who does not feel that our tribute to the dead would be incomplete if this House, of which, by seniority, he was the father, and which for more that two years he has led, were not to offer to his memory to-day its own special mark of reverence and affection. I shall therefore, Sir, propose before I sit down that we should lay aside for to-day the urgent business which has brought us together, and that the House do at once adjourn until to-morrow.

It is within a few months of forty years since Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman took his seat in this Chamber. Mr. Gladstone had just entered upon his first Premiership in the plenitude of his powers and of his authority. A new House, elected upon an extended suffrage, had brought to Westminster new men, new ideas—as some thought—a new era. Among the new-comers there were probably few, judged by the superficial tests which are commonly applied, who seemed less obviously destined than Mr. Campbell, as he then was, for ultimate leadership. There have been men who, in the cruel phrase of the ancient historian, were universally judged to be fit for the highest place only until they attained and held it. Our late Prime Minister belonged to that rarer class whose fitness for such a place, until they attain and held it, is never adequately understood.

It is true that he reached office much earlier in his Parliamentary career than is the case with most politicians. In successive Governments, at the War Office, at the Admiralty, at the Irish Office, and at the War Office again, he rendered devoted and admirable, if little advertised, service to the State.

It is no secret, and it is sufficient proof that he himself had no ambition for leadership, that when he was for the second time a Cabinet Minister, he aspired, Sir, to be seated in your chair. But though he had too modest an estimate of himself to desire, and still less to seek, the first place in the State, it fell to him, after years of much storm and stress by a title which no one disputed; and he filled it with an ever-growing recognition in all quarters of his unique qualifications.

What was the secret of the hold which in these later days he unquestionably had on the admiration and affection of men of all parties and all creeds? If, as I think was the case, he was one of those men who require to be fully known to be justly measured, may I not say that the more we knew him, both followers and opponents, the more we became aware that on the moral as on the intellectual side he had endowments, rare in themselves, still rarer in their combination? For example, he was singularly sensitive to human suffering and wrong doing, delicate and even tender in his sympathies, always disposed to despise victories won in any sphere by mere brute force, an almost passionate lover of peace. And yet we have not seen in our time a man of greater courage—courage not of the defiant or aggressive type, but calm, patient, persistent, indomitable.

Let me, Sir, recall another apparent contrast in his nature. In politics I think he may be fairly described as an idealist in aim, and an optimist by temperament. Great causes appealed to him. He was not ashamed, even on the verge of old age, to see visions and to dream dreams. He had no misgivings as to the future of democracy. He had a single-minded and unquenchable faith in the unceasing progress and the growing unity of mankind. None the less, in the selection of means, in the daily work of tilling the political field, in the choice of this man or that for some particular task, he showed not only that practical shrewdness which came to him from his Scottish ancestors, but the outlook, the detachment, the insight of a cultured citizen of the world.

In truth, Mr. Speaker, that which gave him the authority and affection, which, taken together, no one among his contemporaries enjoyed in an equal measure, was not one quality more than another or any union of qualities; it was the man himself. He never put himself forward, yet no one had greater tenacity of purpose. He was the least cynical of mankind, but no one had a keener eye for the humours and ironies of the political situation.

He was a strenuous and uncompromising fighter, a strong Party man, but he harboured no resentments, and was generous to a fault in appreciation of the work of others, whether friends or foes. He met both good and evil fortune with the same unclouded brow, the same unruffled temper, the same unshakable confidence in the justice and righteousness of his cause.

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had hardly attained the highest place, and made himself fully known, when a domestic trial, the saddest that can come to any of us, darkened his days, and dealt what proved to be a fatal blow to his heart. But he never for a moment shirked his duty to the State. He laboured on—we here have seen it at close quarters—he laboured on under the strain of anxiety, and later, under the maiming sense of a loss that was ever fresh, always ready to respond to every public demand. And, Sir, as we knew him here, so after he was stricken down in the midst of his work, a martyr, if ever there was one, to conscience and duty, so he continued to the end.

I can never forget the last time that I was privileged to see him, almost on the eve of his resignation. His mind was clear, his interest in the affairs of the country and of this House was undimmed; his talk was still lighted up by flashes of that homely and mellow wisdom which was peculiarly his own. Still more memorable, and not less characteristic, were the serene patience, the untroubled equanimity, the quiet trust, with which during those long and weary days, he awaited the call he knew was soon to come.

He has gone to his rest, and to-day in this House, of which he was the senior and the most honoured Member, we may call a truce in the strife of parties, while we remember together our common loss, and pay our united homage to a gracious and cherished memory— How happy is ho born and taught That serveth not another’s will; Whose armour is his honest thought, And simple truth his utmost skill; This man is freed from servile bands Of hope to rise or fear to fall; Lord of himself, though not of lands, And, having nothing, yet hath all.