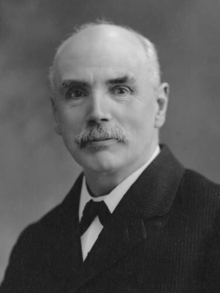

George Barnes – 1921 Speech on the Irish Free State

The speech made by George Barnes, the then Labour MP for Glasgow Gorbals, in the House of Commons on 14 December 1921.

I rise to second the Motion which has been so well and ably put by my hon. and gallant Friend the Member for Chelsea (Sir S. Hoare), and in so doing I need scarcely say that I esteem it a great honour to be called upon to play a small part in the proceedings of this day which I venture to predict will become memorable in our annals. We are called upon to-day to do our part towards ending an age-long controversy which has embittered and poisoned the political life and relations of two countries. We are called upon to-day to offer appeasement both to Ireland and to Great Britain. My hon. and gallant Friend has just said that the efforts to settle the Irish problem have been the undoing of some of our greatest statesmen. Irishmen have been misunderstood by us and we have been continually misunderstood by Irishmen. Ireland has remained an enigma, a weakness and a menace. But to His Majesty the King there came the great good fortune of beginning a new move for peace. His Majesty appealed to the better nature of both sides for forgiveness and forgetfulness of an evil past. He appealed to both sides to get together, to reason together in a spirit of good will, and I venture to say that that appeal has already brought us further on the road to peace and reconciliation than any of the efforts of great statesmen in the past; for the simple reason that it touched the heart. Therefore, in thanking His Majesty the King for the Gracious Speech which has been read to us to-day, we thank him none the less heartily, but rather all the more heartily, for the speech which he made at Belfast, because that speech liberated the kindly feeling on both sides which has brought us together to-day to back up His Majesty’s new effort.

It seems to me the first thing we have to do is to banish rancour from our minds and to approach the question before us in the same spirit as it was approached in that Belfast Speech; to make up our minds as far as we can that Irishmen and Britishers will in future live on terms of amity in the same way as we are living in amity with the peoples of Canada and Australia and of other overseas Dominions. We are here, I fervently hope, on the eve of a settlement of what has ceased to be a mere Irish question, but has become a world-wide problem, because there is not only one Ireland but there are many Irelands. Irishmen, like Scotchmen, have spread themselves over the whole habitable globe; indeed they may be the meek who are destined, according to Holy Writ, to inherit the earth. Whether that be so or not we know that Irishmen have found a home in every land. There is now, therefore, not only an Irish question so far as it used to be regarded, but we have an American Ireland, we have an Australian Ireland, and we have other Irelands, one of which is included within the confines of our own shores. In the City of Glasgow, a part of which I have the honour to represent in this House, it is said that one-fifth of the population is Irish either by origin, by birth or by descent. We have no quarrel with them. We have no quarrel with the Irishmen who are to be found in all the great cities throughout the length and breadth of this country. On the contrary, they join with us in all our activities; they are not only with us but they are of us, because their blood is commingled with our blood, and in these days they are part of the British stock and we to a large extent are part of them.

Therefore for us—in this House or elsewhere—to pass any law or do anything which would make them aliens, which would alienate them, would be to cut away from us that which may became vital both to them and to us. We cannot longer deny, consistently with our professions of democratic Government, consistently with our representative institutions, the right of Irishmen to live in their own country in their own way, and under their own form of Government. We cannot withhold from them the right to manage their own affairs, a right for which they have so long fought. I venture, to say that that is the principle which lies at the bottom of the British Commonwealth of Nations. It is the principle which has been progressively applied to the Dominions overseas until now without conflict or ill-will, they have come to have, and in fact have, absolutely free hands so far as their own internal affairs are concerned. As to the method by which the principle is to be applied in the document now under review, that is a matter which I am not called upon to go into at present, except on general terms. But I may say here that for my part I honestly confess I do not like the creation of new armies and navies. Their multiplication has been one of the tragedies of the past War. Just as honestly I confess I do not like the bare possibility of tariffs being imposed on trade between this country and Ireland. But these things have been thrashed out by those whose business it was to thrash them out. Certain conclusions have been reached, and those conclusions satisfy the requirements of the Admiralty. They leave Ulster free to remain out if she wishes to remain out, but free also to come in, when time has healed old sores and brought forgetfulness of old feuds.

Those, to my mind, are the main principles of the agreement that has been reached. Ireland becomes a free State within the Empire entitled to make her own laws and to enforce them. Ireland becomes entitled to the protection of the British Commonwealth and at the same time is expected to be ready to yield her quota to the protection of other parts of the British Empire. The position of the British Dominions overseas and their relation to the Mother Country is, I suppose, one of the paradoxes of Government. They are free, each and every one of them, to go their own way, and yet they are tied by ties of sentiment and common interests and common protection, and it has been found that those common ties of sentiment, of interest, and of protection are stronger than any mechanical ties ever were or probably ever will be. Yet those Dominions have evolved quite naturally as the result of the progressive application of the principle of democratic freedom, the principle upon which, as I have said, the Empire is based. They have reached the stage which others will reach in due fulfilment of destiny. Ireland, with the exception of Ulster, has now become one of the free Dominions, and Ulster, as I think, is entirely a matter for Irishmen themselves, and not for us.

I hope and believe that this agreement will be ratified by Southern Ireland, and I say so for several reasons. In the first place, and in spite of what has been said within this last day or two in regard to an assumed analogy between this settlement and the, Peace Treaty so far as America was concerned, I have no hesitation in saying that this settlement ought to be ratified, because it bears the signatures of those whom we have been led to believe were the accredited representatives of their country. The agreement was drawn up on that basis, we were told by Mr. de Valera only some two months ago that the men who were here in London were the trusted representatives of a united nation. Therefore, the agreement has been drawn up on that basis, and, that being so, it seems to me that the honour of Ireland is really at stake. In the second place, I think this agreement should be ratified because it does meet and more than meet the aspirations of those Irishmen who have pleaded in this House eloquently and long for the removal of the barriers to the self-expression of their fellow-countrymen. I have heard the late Mr. Redmond and I have read others before him, and I have no hesitation in saying that this agreement goes far beyond anything that has been asked for by any representative Irishman in this House before. Thirdly, I would commend it, because it has the approval of all the political parties in this House. It is not a Party settlement except that the Prime Minister’s good fortune has been to have been in the right place at the right time and to have gathered up and mobilised forces from all political parties. Apart from that, it might be said to be the offer of the nation, tired of fighting and perhaps a little ashamed of its last century’s record.

This agreement is endorsed by all the political parties. The right hon. Gentleman the Member for Paisley (Mr. Asquith), who is the lineal descendant of Mr. Gladstone in this House and the honoured custodian of the Gladstonian tradition, has given it his blessing. The Labour party, which has always stood for Home Rule for Ireland, has claimed it as its own, and, as my hon. Friend who last spoke has reminded us, the Conservatives in the Government have courageously and loyally faced new needs based upon new facts and have accepted the situation. Therefore, it seems to me that there is every probability that there will be no acrimony or discussions of a violent character after this agreement goes through, but, on the other hand, that there is every prospect of good will in its going through. There has been danger sometimes of the Mover or Seconder of the Address to the Throne getting over the border line and saying something which offends the susceptibilities of political parties. To-day there is no such danger, because all political parties are in favour of a settlement.

Lastly, I commend this agreement to all concerned because it corresponds with the pledges given in the Manifesto three years ago. [HON. MEMBERS: “No!”] Well, let me put my point. In the Manifesto issued three years ago by the Prime Minister and the Leader of the House of that time, and upon which the much-talked-of coupon was based, certain statements were made, and amongst them was that if returned again to office the Government was pledged to explore every possible avenue of peace with Ireland on the basis of self-government, with two reservations only, those being the non-separation of Ireland and the non-coercion of Ulster. That statement will be found in the Manifesto. I have it here, but it is not necessary for me to read it. The settlement to which the King’s Speech has led us, and which today we are called upon to endorse, in my humble judgement, fulfils those conditions.

It is true, as my hon. Friend said a little while ago, that it has been reached only after long guerilla warfare, and that it has been reached only after loss of life under distressing and aggravating circumstances. Let me say further that in my judgement, at all events, it is true that its endorsement means some degree of self-mortification on our part and forgetfulness of recent history, but the mortification and forgetfulness are not expected of one side alone. They are expected of both sides. To my mind, the cardinal virtue of the King’s Speech at Belfast was that it appealed to both sides to forgive and forget the past, and, having regard to that speech and the great spirit underlying it, it is inconceivable to me that either side should now refuse the hand of friendship and again revert to barbarism. There is one aspect of it that might he mentioned, and from which, I think, a lesson might be learned. There is in several respects a similarity between our position to-day and that of the United States of America in 1860. The year before Lincoln had been elected upon the principle of non-separation of the Southern States, just as our Prime Minister was elected three years ago on the principle, among other matters, of non-separation of Ireland. Lincoln, in 1860, made an eloquent appeal for peace, but he failed. Addressing the American people, in his first inaugural address, he said:

“We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not be allowed to break our bonds of affection.”

Yet passion did break the bonds and brought, four years of dreadful devastating war, and then there was no separation, because separation, as Lincoln truly said, was impossible. Neither can there be separation between this country and Ireland. Let all of us banish it from our minds. Separation is even less practicable now than it was then, because since 1860 science has bridged the seas and brought nations more into inter-dependent life. Therefore, Ireland to-day is nearer to us in a physical as well as a spiritual sense. She is part of our life and we of hers. Let us, bearing those great facts in mind, accept this great opportunity of peace and appeasement between the two countries. Let us see that, so far as we can make it so, Ireland and Britain shall march forward together as friends and neighbours in the future, separate as regards their internal Government, but indivisible in spirit as separate parts only of a great family of free nations.