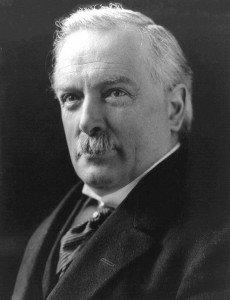

Below is the text of the speech made by David Lloyd George, the then Prime Minister, in the House of Commons on 19 February 1918.

I beg to move, “That Mr. Speaker do now leave the Chair.” In moving that you do now leave the Chair, I have a statement to make to the House on a matter in which not merely the House of Commons but the country are very deeply interested. In doing so, I would like to say that I hope, whatever may be said to-day, this matter will be treated as a question of policy, and not of personalities. If there has been any delay or apparent hesitation in the announcement of any decision by the Government it is not because there is any doubt in their minds in regard to that policy, but because they were very anxious that the decision, when it was announced, should be free from any element of complication about personalities. The Government were extremely anxious to retain the services of Sir William Robertson as Chief of Staff as long as that was compatible with the policy on which they had decided, in common with the Allied Governments, after prolonged consultation at Versailles. It is a matter of the deepest regret to the Government that it was found to be incompatible with that policy to retain the services of so distinguished a soldier. If the policy be right, no personalities should stand in the way of its execution, however valuable, however important, however distinguished. If the policy be wrong, no personalities and no Government ought to stand in the way of its being instantly defeated.

What is the policy? I have already explained to the House—I am afraid rather imperfectly on the last occasion, but to the best of my ability—what is the policy of the Government in this respect. It is not merely the policy of this Government. It is the policy of the great Allied Governments in council. There is absolutely no difference between our policy and the policy of France, Italy, and America in this respect. In fact, some of the conclusions to which we came at Versailles were the result of very powerful representations made by the representatives of other Governments, notably the American Government. That policy is a policy which is based on the assumption that the Allies hitherto have suffered through lack of concerted and co-ordinated effort. There was a very remarkable quotation in yesterday’s “Manchester Guardian,” which, if the House will permit me, I will read, because I think it gives the pith of the whole controversy: Some great soldier once said that to find the real effective strength of an alliance you must halve us nominal resources to allow for the effect of divided counsels and dispersed effort Our purpose and our policy has been to get rid of that halving of the resources of the Allies, so that, instead of dispersion of effort, there should be concentration and unity of effort. There is a saying attributed to a very distinguished living French statesman, which is rather cynical—that, The more he knows of this War, the less convinced he is that Napoleon was a great soldier, for the, simple reason that Napoleon had only to tight coalitions all his life. I ventured some time ago to make an excursion into the general history of the War, in order, without blaming anyone, to point out what the Allies have suffered in the past from lack of co-ordination of effort. You have only to look at 1917, to find exactly the same set of circumstances inevitably affecting, or rather diminishing, the power of that concentration which otherwise would have been possible, in order to counteract the efforts which were made by the Germans, and to counteract the collapse on the Russian front. Anyone who examines closely the events of 1917, as well as the events of the previous year, will find plenty of argument for some change of machinery in order to effect greater concentration than has hitherto been achieved in the direction of the Allied resources. That is the reason why, after the Italian defeat, the Allied Governments, after a good deal of correspondence and of conference, came to the conclusion that it was necessary to set up some central authority, for the purpose of co-ordinating the strategy of the Allies. At the last Conference at Versailles it was decided, after days of conference, to extend the powers of that body.

In discussing the action at Versailles, I am necessarily hampered by the Resolutions arrived at, not merely by the military representatives, but by the separate Governments, that it was not desirable to give any information in regard to the general plan which was adopted. But I think I can, within these limits, make quite clear where controversy has arisen, and ask the judgment of the House on the action of the Government as to the merits or demerits of the dispute. The general principle laid down at Versailles was agreed to whole-heartedly by everybody. I will come later to where controversy arose. There was no controversy as regards policy, but only as to the method of giving effect to it. This obviates the necessity for me to discuss the plan itself, because the House may take it that as far as the plan itself was concerned, there was, and there is now, as far as I know, the most complete agreement. Had there not been, I am sorry to say I could not have gone into it; but it is not necessary. There was agreement as to policy. There was agreement that there must be a central authority, to exercise the supreme direction over that policy. There was agreement that the authority must be an Inter-Allied authority. There was complete agreement that the authority should have executive powers. The only question which arose was as to how that central authority should be constituted. That is the only difference. There was no difference about policy; no difference about the plan; no difference about executive powers; no difference about it being necessary to set up an Inter-Allied authority with control; and no difference about its having executive powers. The only difference was as to how that central authority should be constituted. That was the whole issue. In my judgment—and I will give the facts later—agreement was reached at the Conference, even in regard to that.

Let me give the stages of discussion at the Conference. Several proposals were put forward. We sat for days, and examined those proposals very carefully. I am sure that no one went there with a preconceived plan in his mind. Everybody went with a full desire to find the best method, and not to advocate any particular proposal. All these various proposals were, one after the other, rejected, until we came to the last. I will explain these various proposals, because I can do that without in the least giving, away the plan of operations. The first proposal was favoured in the first instance by the French and the British General Staff. I do not think the American— that is my recollection—or the Italian Staffs took quite the same view; but the French and British Staffs were in favour of the proposal by which the central body should be a council of chiefs of the Staffs. That was the first proposal. I want to show that the very proposal over which controversy raged later was examined at that Conference, and it was the first proposal examined. It was most carefully considered, and I will give the House the case put forward for it, as I want the House to hear on what grounds it was recommended.

It was essential that each of the representatives should be in intimate touch with his own War Office. He must know the man-power, the state of morale, the-medical equipment, shipping, and Foreign Office information, and nobody could know this so well as the Chief of the Staff. Therefore, the new body ought to consist of the Chiefs of the Staffs. It was also naturally felt that there were serious constitutional objections to any system which implied that an Inter-Allied body was to come to decisions affecting the British Army. That is the case which was put forward for a body consisting of Chiefs of the Staffs. The Council examined that very carefully, and discussed it; and let me point out to the House of Commons that this was not a discussion between politicians, but a discussion where all the leading generals were present. The Commanders-in-Chief were there, except the Italian Commander-in-Chief; the French, British, and American Commanders-in-Chief and the Chiefs of the Staffs, as well as the military representatives at Versailles, and the representatives of the Government. It was a free discussion, where generals took part with exactly the same freedom as Ministers. There was no voting; in fact, there was no question of voting. I have no hesitation in saying that, on examination, the proposal completely broke down, and was rejected on the ground of its being unworkable.

I will give the House the reasons why it was regarded as unworkable. The first reason was that the members of the Council felt that the members of the new Executive body which was going to have this great control over co-ordinating the forces of the Allies must not only know about their own armies and their own fronts, but must also be informed of the conditions on all fronts and in all the armies of all the nations, because you are not dealing merely with the British Army, you are dealing with four great armies, and you have to get information from every quarter. Versailles has become a repository of information coming from all the fronts—from all the Armies, from all nationalities, from all the Staffs., from all the Foreign Offices—and that information is co-ordinated there by very able Staffs; and I have no hesitation in saying that they have information there for that reason that no single War Office possesses, because you have information from all the fronts co-ordinated together.

What is the second reason? We felt that this Executive body, in face of the serious dangers with which we have been confronted this year, must be in continuous session, in order to be able to take decisions instantly required. Nobody could tell where a decision would have to be taken. The men who take the decision ought to be within half-an-hour’s reach. Eight hours, ten hours might be fatal. We felt it was essential that whatever body you set up should be a body of men who were there at least within half-an-hour of the time when the Council would have to sit, in order to take a decision. Nobody knows what movement the Germans may make, There may be a sudden move here or there, and preconceived plans may be completely shattered by some movement taken by the enemy. Therefore, it was essential that the body to decide should be a body sitting continuously in session.

The third reason was this: Not merely have they to take decisions instantly, but they ought to be there continually sitting together, comparing notes, and discussing developments from day to day, because a situation which appears like this to-day may be absolutely changed to-morrow. You may have a decision in London, and telegraph it over to Versailles, but by the time it reaches there you may have a complete change in the whole situation. Therefore, we felt it was essential that these men should be sitting together, so that whatever change in the situation took place they could compare notes, discuss the thing together, and be able to come to a decision, each helping the other to arrive at that decision.

There is a further reason. A Council of Chiefs of the Staffs involved the creation of another and a new Inter-Allied body conflicting with Versailles. This point was put by the American delegation with very great force, and it became obvious to everybody there the moment we began to examine the proposal—although on the face of it it looked very attractive—that the functions which the Executive body was to exercise could not be properly performed by a body of Chiefs of the Staffs stationed” in the various capitals. On the other hand, if the Chiefs of the Staffs sat in Paris, it meant that the Governments would be deprived for long periods of their principal military advisers, at a critical time, and at a time when action on other vital matters on other fronts might be required. Therefore, I have no hesitation in saying that the moment it came to be examined— although we examined it with the greatest predisposition in its favour—it was found to be-absolutely unworkable, for the simple reason that the moment the Chief of the Staff went to Paris, he would cease to be the chief military adviser of the Government, and either Versailles would have to be satisfied with a deputy who could not act without instructions, or the Governments would have to be satisfied with a deputy who was not their full military adviser. For that reason, the Supreme Council rejected that proposal with complete unanimity. I think I am right in saying that the proposals were withdrawn. It was felt even by those who put them forward that, at any rate, without very complete changes, those proposals were not workable.

Then it was suggested by the French Prime Minister that it would be desirable for each national delegation to think out some other plan for itself, and to bring it there to the next meeting, and that was done. It is very remarkable that, meeting separately, and considering the matter quite independently, we each came there with exactly the same proposal the following morning, and that proposal is the one which now holds the field. I hesitated for some time as to whether I should not read to the House the very cogent document submitted by the American delegation, which put the case for the present proposal. It is one of the most powerful documents—I think my right hon. Friends who have had the advantage of reading it will agree with me—one of the ablest documents ever submitted to a military conference, in which they urged the present course, and gave grounds for it. I think it is absolutely irresistible, and the only reason I do not read it to the House is because it is so mixed up with the actual plan of operations that it will be quite impossible for me to read it without giving away what is the plan of operations. I only wish I could. I hesitated for some time, being certain if I read that to the House of Commons, it would not be necessary for me to make any speech at all, because the case is presented with such irresistible logic by the American delegation that I, for one, do not think there is anything to be said against it, and that was the opinion of the Conference.

What happened? We altered it here and there. There was a good deal of discussion. It was pointed out that there was a weak point here, and a weak point there. Then someone suggested how to improve it. It took some hours, but there was not a single dissentient voice so far as the plan was concerned. Everybody was free to express his opinion —not merely Ministers, but generals. The generals were just as free to express their opinions as the Ministers, and as a matter of fact Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig did call attention to what we admitted was a weak point in the proposal. I think he called attention to two points. We soon realised that there were weak points, we promised to put them right, and some of the time occupied was time occupied in adjusting the arrangements arrived at at Versailles to meet the criticisms of Sir Douglas Haig. They were points in regard to the Army and the Army Council, constitutional points, not points that went to the root of the proposal itself. I want the House again, at the expense of repeating myself, to recollect that this passed the Versailles Council without a single dissentient voice as far as all those who were present are concerned, and, as far as I know, it was completely accepted by every military representative present. I reported to the Cabinet as soon as I returned the terms of the arrangement. I am not sure that it had not been circulated beforehand. I rather think it had, and then I made my report to the Cabinet. Sir William Robertson was present, and nothing was then said or indicated to me that Sir William Robertson regarded the plan as either unworkable or dangerous.

Therefore, I think I was entitled to assume that, although some of the military representatives at the beginning of the Conference would have preferred another plan, that they, just like our-selves, had been converted by the discussion to the acceptance of this plan. There was nothing to indicate that anyone protested against the plan which was adopted at Versailles. During the week— that is, the week after I returned from Versailles—the Army Council considered the arrangement, and made certain criticisms from the constitutional point of view. I considered these very carefully with the Secretary of State for War, who has throughout put Sir William Robertson’s views before the Cabinet with a persistent voice, and I considered very carefully with my colleagues all these constitutional points. Having considered them, we made certain arrangements, with a view to meeting the constitutional difficulties of the Army Council. I will give substantially the arrangements which we made, and which I understood from the Secretary of State for War completely removed the whole difficulties experienced by the Army Council in the carrying out of the arrangements. I was naturally anxious that this arrangement should be worked whole-heartedly by the whole of the military authorities, whether here or in France. I was specially anxious that the Commander-in- Chief, who is more directly concerned in the matter than even the Chief of Staff, because it affected operations, perhaps, primarily in France, should be satisfied that the arrangements that were made were such as would be workable as far as he was concerned. Therefore, before I arrived at this arrangement, I invited him to come over here. I had a talk with him, and he said that he was prepared to work under this arrangement. I will give the arrangement: The, British permanent Military Adviser at Versailles is to become a member of the Army Conicl— That is, in order to get rid of the constitutional difficulty that someone may be giving an order about British troops who is not a member of the Army Council. He was, therefore, made a member of the Army Council. That was agreed to on all hands.

He is to be in constant communication with the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and is to be absolutely free and unfettered in the advice he gives as a member of the Board of Military Representative; at Versailles. It would be idle to send a man there simply with instructions in his pocket that he is to agree to certain things and to nothing else. If he goes there, he must go to discuss with his colleagues, who are equally free and unfettered, to consider the facts, and to give advice according to what he hears from the others, as well as on the facts submitted to him— He is to have the powers necessary to enable him to fulfil the duties imposed upon him by the recent Versailles decision. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff is to hold office under the some conditions and with the same powers as every Chief of the Imperial General Staff up to the appointment of General Robertson, remaining the supreme military adviser of the British Government. I want the House to take in that fact. It was part of the arrangement that the Chief of the Staff was to remain the supreme military adviser of the Government— He is to accompany Ministers to the meetings of the Supreme War Council as their adviser, and is to have the right to visit France and consult with any or all of the military representatives of the super me War Council. What does that mean? It means that the representatives at Versailles must have the most perfect freedom to discuss plans and to recommend plans. If the Commanders in Chief do not approve of them—because, by the arrangement they were to consult, and be in constant communication with, the Commanders in Chief—or, if there was any difference of opinion among the various representatives, the Governments were to decide. There is no derogation of the power of the Government—none. In that case, who is to advise the Government? The advice to the Government would be given by the Chief of the General Staff, so that if there were a meeting of the Supreme War Council to decide differences of opinion between either the military representatives or the Commanders -in-Chief, the Government decide upon the advice of the Chief of the General Staff. Do not let anyone imagine that differences of opinion are going to begin now. I do not want to go into the matter, but difference of opinion is inevitable. It is no reflection upon them. They are men of independent mind, they are men of strong character; they are men of definite opinions, and, of course, there are differences of opinion, and when there are differences of opinion now, there is no one to decide but the Government, and the Chief of the Imperial Staff is still to be the supreme adviser of the Government in any differences that may in these circumstances arise. That is the position as far as the decision at Versailles is concerned.

We were under the impression that all the difficulties, the constitutional and technical difficulties, had been completely overcome by this document, which had been shown to Sir Douglas Haig. Sir William Robertson, unfortunately, was away at the time—I think he was at Brighton—I am sorry now to learn that he was ill. At any rate, he was away, otherwise he would have been present at the Conference. We were under the impression—I certainly was under the impression—that the last of the difficulties had been removed, and, having been removed, as I was under the impression that Versailles had become the more important centre for decision, the Government decided to offer the position to Sir William Robertson. It was only afterwards that, at any rate, I realised that Sir William Robertson was unwilling to acquiesce in the system, and that he took an objection, not on technical grounds or on constitutional grounds, but on military grounds, to the system which Versailles had decided unanimously to adopt. I certainly had not realised that he took that view. We offered him, first of all, the position at Versailles. He could not accept it. We then offered him the position of the Chief of General Staff, with the powers adapted to the position which had been set up at Versailles. That, I am sorry to say, he also refused. He suggested a modification of the proposals, by making the representative at Versailles the Deputy of the Chief of Staff. We felt bound, after consideration, to reject that proposal, for two reasons. It involved putting a subordinate in a position of the first magnitude, where he might have to take vital decisions, under instructions given him beforehand, before the full facts were known, before either had heard what the other representatives had got to say, before he even knew what alternative plans might be put forward by the representatives, or by altering those instructions after consultation with the Chief, who was a hundred miles away, and who was not in touch with the every-day developments, or with the arguments that had been advanced at that particular Conference — an impossible position for any man to take up.

The second reason is this: If you send a deputy there, the representative of the British Army would be in an inferior position to any other member of the Council, and he could not, therefore, discuss things on equal terms. We felt it was, essential that the British representatives should be equal in responsibility and authority to the representative of any other country on that body. I know it is said that General Foch was put on that body. General Foch is within twenty-five minutes of Versailles, and, if any emergency arose, within twenty-five minutes he could be present. That is not true of any other Chief of Staff. He can be at his office in the morning, and in twenty-five minutes he can be at Versailles. There is no other Chief of Staff to whom that would be in the least applicable. Travelling under any conditions from here to Paris involves time, and it is not so easy to do it now. You have got to consider a good many things when you consider what time you can go. You cannot say, start now and be there in eight hours. In a war that makes all the difference—it is vital. Therefore, we considered that it was a totally different position.

The French felt so strongly that you cannot do your business by deputy that they took away the man they had, and put General Foch there. They knew that you cannot have deputies acting on the Board. You have to get the man himself, whoever he is, to take the position. I am sorry to take up the time of the House, but I want to give a very full explanation, as full as it is compatible with not giving away information to the enemy. Sir William Robertson came to the conclusion that, under the conditions laid down, he could not accept either position, and the Government, with the deepest and most genuine regret, found itself obliged to go on without him. We had to take the decision, and it was a very painful decision, of having to choose between the policy deliberately arrived at unanimously by the representatives of the Allied Powers, in the presence of the military advisers, and of retaining the services of a very distinguished and a very valued public servant.

When it came to a question of policy of such a magnitude, we were bound to stand by the arrangement to which we had come with our Allies. Let me say at once that I do not wish in the least to utter a word that would look like a criticism of the decision of Sir William Robertson that he could not see his way to carry out the arrangement. There is not a word to be said about the decision to which he came. It is better that it should be carried out by those who are thorough believers in the policy concerned. With great public spirit, he has accepted a Command which is certainly not adequate to the great position he has occupied, and I wish there had been something else that would be more adequate to his great services. I would like to say just one word about Sir William Robertson. He has had a remarkable and a very distinguished career, and he is now in the height and strength of his powers; in fact, they are only in the course of development. He has great capacity and great strength of character, he is a man of outstanding—and, if I may say so, as one who has been associated with him for two or three years—not merely outstanding, but a most attractive personality. During the whole of those two years, so far as our personal relations are concerned, not merely have they been friendly, but cordial. During the whole time of this final controversy not a bitter word has been said on either side, and at a final interview—where I did my best to urge Sir William Robertson to take one or other of these alternatives—we parted with expressions of great kindliness. It is a matter of very deep regret to me. All the hesitation that has taken place has taken place because the Government were trying this and trying that, in order to secure Sir William Robertson’s acceptance; and although I knew it was laying the door open to the criticism that the Government did not know its own mind, I preferred that to anything which would lay us open to the charge that we were in the least hustling Sir William Robertson. I do not regret that the delay has taken place.

I have always recognised the difficulties in the way of securing co-operation between Allies. There are practical difficulties— genuine practical difficulties. You have to reconcile the unity of the Allies with the unity of the Army. There were some friends of ours who undoubtedly had honest misgivings that the arrangement we made, whereas it might secure the first, was imperilling the second. That would be a misfortune. You would not help the former in that case, and I fully realised that. Let me say this, if the House were to accept the Government’s explanation to-day, I would not regard it as a mandate not to take all the necessary steps compatible with the main purpose of Allied unity to remove every legitimate cause for anxiety on that score. Quite the reverse. I propose to invite from the highest military authorities suggestions for the best means of removing any possible anxiety in the mind of anyone that in any scheme put forward in order to secure concert and combined action between Allies, you are not doing something to impair the efficiency and command of your own Army. Therefore, we shall certainly pursue that course, and if any suggestion comes from any military quarter to make the thing work even better from that point of view, certainly not merely shall we adopt it, but we shall seek it, and we mean to do so.

There are other difficulties, not merely practical difficulties—there are difficulties due to national feeling, to historical traditions. There are difficulties innate in the very order of things. There are difficulties of suspicion—the suspicion in the mind of one country that somehow the other country may be trying to seek some advantage for itself. All these things stand in the way of every Alliance. There are also difficulties due to the conservatism of every profession—I belong to a profession myself, and I know what it means—the conservatism of every profession, which hates changes in the traditional way of doing things. All these things you have always to overcome when there is any change that you make, and they ought not to be encouraged too much on these lines. I agree that reasonable misgivings and reasonable doubts ought to be removed. If there be real difficulties, those ought to be examined and surmounted. But suspicion, distrust— those ought to be resolutely discouraged among Allies. Trust and confidence among the Allies is the very soul of victory, and I plead for it now, as I have pleaded for it before.

We have discussed this plan, and re-discussed it with the one desire that our whole strength—our whole concentrated strength—should be mobilised to resist and to break the most terrible foe with which civilisation has ever been confronted. I ask the House to consider this: We are faced with terrible realities. Let us see what is the position. The enemy have rejected, in language which was quoted here the other day from the Kaiser, the most moderate terms ever put forward, terms couched in such moderate language that the whole of civilisation accepted them as reasonable. Why has he done it? It is obvious. He is clearly convinced that the Russian collapse puts it within his power to achieve a military victory, and to impose Prussian dominancy by force upon Europe. That is what we are confronted with, and I do beg this House, when you are confronted with that, to close down all controversy and to close our ranks.

If this policy, deliberately adopted by the representatives of the great Allied countries in Paris, dose not commend itself to the House, turn it down quickly and put in a Government who will go and say they will not accept it. But it must be another Government. But do not let us keep the controversy alive. The Government are entitled to know, and I say so respectfully, to know to-night whether the House of Commons and the nation wish that the Government should proceed upon a policy deliberately arrived at, with a view to organising our forces to meet the onset of the foe. For my part—and I should only like to say one personal word—during the time I have held this position, I have endeavoured to discharge its terrible functions to the utmost limits of my capacity and strength. If the House of Commons to-night repudiates the policy for which I am responsible, and on which I believe the saving of this country depends, I shall quit office with but one regret—that is, that I have not had greater strength and greater ability to place at the disposal of my native land in the gravest hour of its danger.