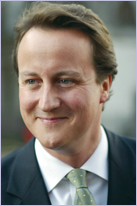

The speech made by David Cameron, the then Leader of the Opposition, on 24 January 2008.

It’s a great honour to be here in such distinguished company.

Many, perhaps most of you, run large organisations with a significant impact on our world and you experience on a daily basis all the responsibility that goes with leadership.

One of the most important aspects of leadership, as I’m sure you all recognise, is to see the future clearly, and to understand the possibilities of the future for the organisation you lead.

Of course it’s vital to focus on the short-term, day to day detail.

But not at the expense of a long-term vision.

It’s the same in politics.

My daily life in politics is a short-term battle.

In Parliament, making sure I hold the Prime Minister properly to account.

Around the country, making sure I meet the people who matter.

On the media, making sure I get my Party’s message across.

But real success comes when you set out a clear, long-term vision.

And that means a clear understanding of the future and its possibilities.

That is the great value of Davos – and of evenings like this.

They give us the chance to share perspectives on the future, and to explore how we might collectively shape it. And tonight I would like to share with you my sense of the three big trends that are shaping our world – and how to make sure make the right choice about how to respond.

FREE TRADE OR PROTECTION

The first big choice we have to make, and perhaps the most immediately significant at this time of uncertainty in the global economy, is an economic one.

Are we going to be on the side of free trade, or protection?

You may think that argument has been settled.

You may think that the great benefits of globalisation – the consistent rise in living standards; the lifting of billions of people around the world out of poverty; the opportunities we enjoy today that would have been unimaginable for our grandparents…you may think that because of these things, and because it is so widely acknowledged that trade is the greatest driver of prosperity the world has known…there is no choice to be made.

But there is.

Every generation has to fight and win the argument for free trade and open markets.

Just look at the Presidential election in the US.

On both sides of the political divide, there are candidates advocating protectionist policies.

There is one clear exception – and I admire him a great deal for his stance.

Senator John McCain did my Party the great honour of addressing our annual conference two years ago, and we saw then the courage and conviction that saw him go to Michigan and tell the voters directly that the old jobs weren’t coming back and that protectionism was no answer to today’s economic problems.

He didn’t win the primary, but he certainly won a lot of respect.

China also has protectionist tendencies.

So does India.

Other countries too.

Failure of Doha risks severe loss of momentum towards the global free economy.

Bilateral deals risk creating a complex thicket of regulations.

We must be clear about our position.

Yes to free trade. No to protection.

Globalisation is good for Europe, good for America, good for the world.

As politicians, our actions must match our rhetoric.

No buying off domestic opinion with subsidies and barriers.

At a time of global and economic uncertainty and of financial instability we must not pander to people’s fears by peddling false hopes of protectionism.

In years to come, the world will look back at this period, and there will be heroes and there will be villains.

The heroes will be those who held their nerve and stood up for free trade. The villains will be those who tried to push us over this tipping point and down the dangerous path of protectionism.

Our job is to educate people, not deceive them with false remedies.

So we need to fight to end immoral subsidies in the developed world, that cripple developing economies by flooding them with cheap imports and preventing them from competing on a level playing field.

It’s completely counterproductive to be increasing aid with one hand, and then completely undermining it with the other.

But the trade policy of developing countries matter too.

In Western Europe 63 per cent of trade by countries is with other countries in Western Europe.

Among North American countries it is 40 per cent.

But in 1997, the World Bank found that the figure for African nations is only 10 per cent.

This is a missed opportunity – and it’s holding Africa back.

The key problem is the persistence of high African trade barriers.

This is preventing specialisation between African nations, hindering productivity growth, and clogging up Africa’s wealth creation engine.

So just as we must be bold when it comes to boosting global trade, the same is true of intra-continental trade – particularly in Africa.

POWER IS MOVING SOUTH AND EAST

The second test is how we respond to the historic shift in power that is now taking place.

The world’s centre of gravity is moving from the west to the south and the east.

Clyde Prestowitz in his book Three Billion New Capitalists points out that China and India are emerging as major industrial powers at a rate that will see China as the world’s greatest economy in 20 years and India taking over China’s place in 40-50 years.

Other countries such as Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa are also on the fast track to economic development.

The paradox at the root of globalisation is that as the world becomes more and more integrated, so power has become more and more widely distributed.

Wealth, knowledge, military might – these are no longer monopolies or duopolies.

They have been scattered across the globe and require us to engage with people from many different parts of it.

This applies just as much to emerging powers as to established ones.

The more you look at Africa, the more you realise how important it is to China, the biggest importer of African minerals. That gives her a huge stake in stability in the region.

When an oil installation is attacked in the Sudan, it matters to China.

Angela Merkel said that Germany’s true frontier is in the Hindu Kush.

She’s right.

Radicalisation in Pakistan affects all of us.

And we also know that India is a key player in everything that happens in the region.

These are the new realities.

Economic power is going south and east whether we like it or not.

Political power will inevitably follow.

The question is: what should we do about it?

Some people argue that America and Europe should form a defensive bloc and defend their imperium for as long as possible. I disagree.

It’s not a matter of ‘us’ v ‘them’.

In a complex world flexibility is the key.

The future of global politics lies in networks, not in blocs. The bloc mentality is not only outdated, it’s a recipe for conflict. The emerging powers are not only different to western nations; they are different from each other.

As each of their stars rises in this new world, so their stake increases in preserving global security and stability. If we want countries like these to assume greater responsibility, we in the west must respond appropriately. We must treat each individually, and with respect.

A new internationalism means creating a new framework where good governance and the rule of law are genuinely rewarded. It means bringing rising powers – Asian giants such as India and China, but also Brazil and others – onto the top table.

It means giving them a stake in world affairs by involving them more formally in the decision making process.

That’s why, for example, I called last year for China and India to be given permanent seats on the UN Security Council. Making partners out of the emerging powers rather than forming a bloc against them is the right way forward. That is not to deny that there is merit in Europe and America moving closer together. I have said that the 21st century is the centre-right century.

One of the reasons is that the centre-right understands the new role of the transatlantic alliance in the new world that is emerging.

Most forecasts suggest that, by 2050, the EU and NAFTA will each be only mid-sized economic blocs in a world increasingly dominated by South Asia .

As Edouard Balladur and other leading thinkers of the centre right are beginning to point out, if we wish to retain Western negotiating power, we will need to think radically about how to deal with this new situation.

I believe that the time has indeed come to stop thinking of the two sides of the Atlantic as separate blocs and to begin considering, instead, how we can bring the EU and North America together into a true single market.

A new economic alliance, building on the work that is already underway to harmonise market regulation between the two sides of the Atlantic, can provide the West with two 21st century advantages:

– first, the increased growth that comes from deeper and wider free trade internally;

– and second, the scale that will enable us to be at least equal partners with the South Asians.

Centre-right free trade economics, and centre-right atlanticism, can together give the West its proper place in the coming century.

FROM BUREAUCRATIC TO POST-BUREAUCRATIC AGE

The third test is whether we recognise that we are moving from a bureaucratic to a post-bureaucratic age. The decentralised inter-connectivity that provides the best hope for global security and prosperity applies just as much to our domestic situation.

For too long European governments believed in ever-larger states as the best mechanism for delivering a better quality of life.

Although Britain doesn’t have the biggest state sector in Europe it does have one of the most centralised.

Our societies are changing.

We are moving from the Bureaucratic to the Post-Bureaucratic age.

The bureaucratic era was about faith in centralised administration.

Often motivated by noble impulses, to iron out inequalities and differences, to promote fairness and progress, to achieve value for money; central planners asserted a strong role for the top-down central state.

This trend was brilliantly exposed by Friedrich Hayek in his seminal book, the Road to Serfdom.

In it he argued that the logical consequence of the rise of the central planner, however well-intentioned, was the loss of individual freedom. We know this all too well in Britain which today is one of the most centralised countries in the democratic world.

I don’t think many of you who are not from the UK would believe the degree to which a minister in our national government has top-down control of what happens in our schools, hospitals, roads and public spaces.

I’m convinced that this cannot be sustained.

The countries of the west need smaller states.

State spending of 45 per cent plus of GDP is unsustainable.

People have ever higher aspirations in our new world.

They expect more.

Why? Because they now experience high levels of service in so many other aspects of their lives.

Government cannot keep up with rising expectations. Taxpayers bitterly resent paying ever higher percentages of income to the state getting such poor value for money.

At the same time as trying to meet these demands, western governments have to look over their shoulders at the lean, mean competition from the rising economies of the south and the east.

Something has got to give.

This raises profound questions about how basic services are provided. Either government must ask for less or give more.

Giving more is not an option because central government is too cumbersome an instrument to deliver quality services. Far better to let people keep more of their money and use it to provide what they and their families need.

That’s the new world of freedom.

And right at the heart of this new world is freedom of information – in the broadest meaning of that term.

In recent years technological advance, supported by a liberal regulatory regime, has transformed the amount of information that’s available…

…the number of people who can get hold of it…

…and the ease with which they can do so.

True freedom of information makes possible a new world of responsibility, citizenship, choice and local control. By understanding this reality and adopting this agenda, western leaders can equip their countries for the challenges ahead.

CONCLUSION

Business too must understand these challenges if it is to thrive.

Today it isn’t just a matter of increasing profits.

It’s about how these profits are made.

That’s why Corporate Social Responsibility matters, whatever its critics may claim.

Setting up a couple of community projects where you use some of your wealth to do good doesn’t count as ‘social responsibility’ unless the wealth itself was gained responsibly.

Would it make any sense to say to media companies that you can simply meet your obligations for social responsibility – to be a responsible corporate citizen – through community projects which had nothing to do with your actual product?

Imagine if we took this approach with McDonalds or a mining company.

Is it really enough to say that you can put anything you like in your burgers, or do anything you want to the environment when digging for precious metals…. “That’s ok, as long as you are doing some other charitable things at the same time”?

Of course not.

Being a responsible business is not just about not doing bad things – it’s about doing good things.

We are all in this together, and if we work together, understand our responsibilities and embrace the opportunities of the modern world, there is no limit to what we can achieve.

Let me conclude by putting it another way, more than 40 years ago, John F. Kennedy said:

“Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your county.”

It was a noble cry then, and remains so today. But when he made it people didn’t really have the information they needed, the knowledge to make choices and the power to take control of their lives. Today they do, they have that information, that knowledge, that power and so a new generation of politicians can help make that noble dream a reality.