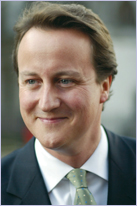

David Cameron – 2007 Speech on Islam and Muslims

Below is the text of the speech made by David Cameron, the then Leader of the Opposition, on 5 June 2007.

I was unable to attend yesterday, but Sayeeda Warsi, Dominic Grieve and the chair of one of my policy group’s, Pauline Neville-Jones, were, and have relayed to me some the key issues that were raised.

The need to define our common values.

The impact of modernity on traditional Islamic societies.

And the need to build greater understanding of Islam by others – and of Western society and culture by Muslims.

These are questions that fall under the wide-ranging disciplines of political science, theology, and sociology, but what underpins them all is a question as old as humanity itself: how do we live together?

In this country, there have been times when this question has been uppermost.

While conflict between Catholics and Protestant in Britain was bloody, we were spared the worst excesses witnessed on the continent.

The Glorious Revolution and the two Jacobite rebellions were periods of crisis for the coherence of our country.

Subsequent Catholic emancipation was a long and slow process, but ultimately successful.

The incorporation of East European Jewish immigrants, particularly a 100 years ago, and the Ugandan Asians 30 years ago can also be regarded as successes in integration into a British identity.

Each time, Britain has been able to rise to the challenge and sustain our coherence and unity.

We have done so through a combination of a steadfast faith in our institutions and values, such as freedom under the rule of law, pluralism and tolerance….

……and because society – not only the majority community but the minority community too – were prepared to stand together as one.

There is no reason to think we cannot do the same today.

Security Threat

The evil terrorist campaign we have witnessed in recent years has revealed the existence of a murderous ideology which distorts Islam and plays on a range of grievances to turn a small number of young men into revolutionaries.

As the Grand Mufti of Egypt said yesterday, “there is nothing in Islam that could ever justify these blatant acts of aggression”.

Confronting the false basis of this perversion of Islam is one part of what needs to be done.

Ensuring an appropriate security response is another.

But today I want to talk about the third element: community cohesion.

Promoting community cohesion should indeed be part of our response to terrorism.

But cohesion is not just about terrorism and it is certainly not just about Muslims.

Promoting integration will help protect our security.

But too mechanistic a connection between these objectives will make it harder to achieve both, by giving the impression that the state considers all Muslims to be a security risk.

After all, it is a tiny minority of British Muslims who support terrorism.

And fewer still who are likely to plan or commit terrorist atrocities.

Cultural Separation

That’s why, in discussing community cohesion today, I want to focus on another significant trend: cultural separation.

There has been a rise in what the French scholar Olivier Roy calls ‘religiosity’ among second or third generation Muslims of immigrant origin.

Of course we should welcome, not condemn, people who choose in a free society to express their religious belief.

But what should most definitely concern us is when heightened religious observation is accompanied by a rise in cultural separatism.

As the Grand Mufti said yesterday, “Islam calls on Muslims to be productive members of whatever society they find themselves in. Islam embodies a flexibility that allows Muslims to do so without any internal or external conflict.”

Therefore, cultural separatism is something we must all work hard to resist and reverse.

Again, not just because it relates to our security concerns.

Although all terrorists are cultural separatists, not all cultural separatists are terrorists.

But though cultural separatists eschew violence, many find it hard to accept what has happened with 7/7 and other plots. In short, they seem to be in denial.

I recently visited a mosque in Birmingham and got some depressing questions about who was really responsible for 9/11 and even 7/7.

That it was a CIA plot.

That Jews had been told to leave the twin towers.

When it comes to 7/7, there was real scepticism about the suicide bomber videos being fake or not.

Indeed, the poll by Channel 4 news out today suggests that one in four Muslims in this country think Government agents staged the July 7th bombings.

This is a real problem which we have all got to get to grips with.

And some recent opinion polls have suggested that we may have a growing problem of cultural separatism: in other words, the next generation of British Muslims are more separate from mainstream opinion than their parents.

For example, in a recent survey of 16-24 year old Muslims in this country, 36 percent believed if someone converts from Islam they should be punished by death.

Now, in a free society, we are all allowed our own opinions.

What’s more, as individuals, we can legitimately challenge the status quo as long as it is done within the rule of law.

But I think we should be able to say confidently, and without wanting to cause offence, that some of these views are contrary to the principles of freedom and equality that we hold dear in this country.

In that respect, they must be challenged.

And I do not want to shy away from my responsibility of making this clear.

But perhaps a much more telling statistic, and alarming indictment on the cultural separation in our society, is that 31% of all Muslims in this country feel they have more in common with Muslims in other countries than they do with non-Muslims in Britain.

This cannot be explained simply in terms of the bonds of kinship which anyone will feel to the homeland of their ancestors.

There is something much deeper at work here:

A feeling of alienation.

A disillusionment with life in this country.

And an ambiguity over what it is to be both Muslim and British.

It is now absolutely vital that we address this trend.

After all, we should acknowledge that those who feel simply disillusioned and disaffected today can turn to something much more sinister, and much more subversive, tomorrow.

Indeed, as Peter Clarke, Deputy Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police recently said, “one of the most worrying” things he has come across in his job “has been the speed and apparent ease with which young men can be turned into suicidal terrorists, prepared to kill themselves and hundreds of others.”

What’s more, it is these people who are the first line of defence in the battle against those extremists who are actually planning attacks.

They are their cousins, brothers and sisters, and it will harder for them not only to apply the social pressure, but also indeed to recognise particularly radical philosophies contrary to the British way of life, if they themselves remain divorced from life here.

In a moment, I will explain how I think we can reverse this trend.

But first, I want to explain why I think it has happened.

Politics of Identity

Of course, there are many factors that need to be taken into consideration.

First, and not least, the impact that poverty and poor life chances have on someone’s sense of isolation and belonging.

Second, racism and bigotry has done much to harm community relations.

You can’t even start to talk about a truly integrated society while people are suffering racist insults and abuse, as many still are in our country on a daily basis.

Third, we have to recognise that for some young Muslims, their sense of belonging to a global Muslim community is heightened by the perception that Islam, around the world, is under attack.

They see the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

And the continued failure to settle the Palestinian question.

We have to explain patiently and carefully that in Iraq and Afghanistan we are supporting democratically elected Muslim leaders.

And that in a democracy, disagreement with foreign policy can never justify violence or terrorism.

We must explain that in the Middle East we are pushing hard to get the peace process restarted.

At the same time, we must be careful not to link these issues together.

Some of the rhetoric about the ‘War on Terror’ has helped to give this impression.

As I’ve said before, this can play into the hands of those – like al-Qaeda – who want to divide the world in two.

The reality is that we should disaggregate these issues and deal with them one by one, with the humility and patience.

And a fourth factor which has helped foster this lack of belonging for many young Muslims in the UK today is the influence of a number of Muslim preachers that actively encourage cultural separatism.

One such preacher is Yusuf al’Qaradawi, who though he encourages Muslim participation in political life in the UK, says he wants to create an ‘Islamic Movement’ which he defined as “the organised, collective work undertaken by all the people to restore Islam to the leadership of society and the helm of life [in] all walks of life”.

What’s more, there are some Muslim organisations that advocate complete non-participation, especially in political life, as part of being a good Muslim.

Such encouragement is nothing short of passive resistance to our values deliberately designed to keep the Muslim community detached and separate- as outsiders in their own country.

This is helpful to no one.

It helps serve as a recruiting sergeant for the BNP, who can play up to the politics of fear by demonising an ‘other’ which refuses to play its part in wider society.

And those Muslim communities that choose to hold themselves apart will struggle to prosper and thrive in this country.

This was a point raised by Mufti H.E. Mustafa Ceric yesterday : the need for Muslims and the host nation to go forward on a shared, not independent, basis.

So poverty, racism, the perception that Islam is under attack and the influence of preachers that encourage separation all have a part to play in explaining why some Muslims hold views contrary to values we hold dear in this country and seem so disillusioned with life in Britain.

But I want to focus on a fifth reason in particular: the question of identity.

There are two, mutually reinforcing, factors at work here.

First, what we are witnessing is a rise in Muslim identity and consciousness.

Olivier Roy explains that this is a result of Islam becoming ‘de-territorialised’ – that is, established beyond its customary geographical and social backdrop.

In traditional Muslim societies, one’s identity is everywhere: local schools, music, arts, family, and the legal system.

But as Roy goes on to say, once Muslims leave these traditional societies through emigration, their identity is no longer supported by society at large.

Within this framework, many first generation immigrants happily fit in with the norms and customs of their new homeland.

But they do so while not making a full break with their place of birth, bringing with them traditional habits and beliefs.

But it is their children who can feel more rootless: unable to identify fully with neither the traditional practices of their home life nor the cultural norms of modern Britain.

It is their search for an identity which makes them associate more readily with the global ummah – the worldwide Islamic community.

It is this which can lead to a depressing sense of isolation from their country of birth.

At its very worst, it can lead to extremism and violence.

This process of rising Muslim consciousness has been accelerated by the creed of multiculturalism, which despite intending to allow diversity flourish under a common banner of unity, has instead fostered difference by treating faith communities as monolithic blocks rather than individual citizens.

The result has been what Amartya Sen calls ‘plural monoculturalism’: a system in which people are constantly herded into different pens, with respective grievances and rights.

As a result, Bangladeshis, who have their own distinctive language and culture, are now grouped together with people from Iran to Indonesia….

….. reinforcing their sense of separateness on strength of their religious belief alone.

This rise in Muslim consciousness has been reinforced by a second, parallel, factor at work: the deliberate weakening of our collective identity in Britain.

Again, multiculturalism has its part to play.

By concentrating on defining the various cultures that have come to call Britain home, we have forgotten to define the most important one: our own.

We hear it more and more: what does it mean to be British?

We are less sure how to articulate an answer to that question than we ever have been in history.

Just recently, I stayed for a couple of nights with Abdullah and Shahida Rehman in Birmingham.

I spent a lot of time talking to them and their family, and also the wider Muslim community in the area.

Time after time I heard people talk about the uncivilised behaviour and values they see all around them.

Drugs, crime, incivility are – we have to admit – an all too common part of life in modern Britain.

We have to understand that integration is a two-way street. It is about more than immigrant communities, ‘their’ responsibilities and ‘their’ duties.

It has to be about the majority population too- the quality of life we offer, our society and our values.

Building a Positive Society

The challenge now is to create a positive vision of a British society that really stands for something and makes people want to be a part of it.

A society in which we are held together by a strong sense of shared identity and common values.

A society which encourages active citizenship, not a passive standing on the sidelines.

A society which people are not bullied to join, but are actively inspired to join.

It is about creating a framework of values in which people – all people – in our country feel they are part of a shared national endeavour, a positive purpose.

And I believe there are two key priorities in making this happen.

First, we need a clear sense of our British identity and ensure it is open to everyone.

Second, we need to build a society where people really feel they have the power to shape their own destiny.

Building Identity

Let me take each in turn.

First, a society that has the ability to inspire its citizens is one with a strong sense of history and values.

That’s because history and values together shape our identity.

History revolves around institutions, buildings, symbols; a sense of where you have come from and where you are going to.

Think of America.

Of course America is not perfect.

But it does succeed in creating, to an extent far more evident that we have achieved here, a real sense of common identity – about what it means to be an American.

Freedom. Family. Opportunity and community.

Now, this is not to say we in Britain have neither history nor values. We have plenty of the former and a keen sense of the latter.

The difference is that in America, this identity is positively and actively embraced by nearly everyone, regardless of his or her ethnic background and religious affiliation.

You can see it in daily rituals like the Pledge of Allegiance.

In the strong sense of emotional attachment and reverence towards Mount Rushmore and Arlington Cemetery.

And you can see it in America’s coming together on Independence Day and Thanksgiving.

It is this strong sense of inclusive identity that has helped make so many people feel part of American society.

In Britain, we have to be honest: we have failed to do the same.

We have not opened up our sense of citizenship to all those that have come to live here.

Of course the vast majority of families of recent immigrant origin do feel a strong sense of citizenship and what it is to be British.

Indeed, my time in Birmingham with the Rehmans showed that if we want to remind ourselves of British values – hospitality, tolerance and generosity to name just three – there are plenty of British Muslims ready to show us what those things really mean.

The problem is some do not.

That’s because much of this transmission of our identity is unspoken and instinctive.

‘Unspoken’ English, as it were, can be the most difficult language to learn if you come from elsewhere.

Now this does not mean we have to adopt flag-raising ceremonies or ritualistic pledges of allegiance to the monarchy.

But we can start by ensuring history is taught properly in schools.

This does not mean we have to gloss over all the things we are not entirely proud of, but we should at least celebrate the many positive things Britain has achieved both at home and abroad.

After all, you do not earn respect by constantly denigrating and repudiating your own culture

This must include teaching our children about concepts like the rule of law, free speech, freedom of the individual and parliamentary democracy.

We can also help foster a shared sense of identity by making sure immigrants can speak English.

Today, we have communities where people from different ethnic origins never meet, never talk, never go into each others’ homes.

Ultimately, it is an emotional connection that binds a country together. It is by contact that we overcome our differences – and realise that though our origins and our cultures may vary, we all share common values.

The most basic contact comes from talking to each other: and if people cannot speak the English this becomes near-impossibe.

And let’s be clear: when we say a common citizenship must be open to everyone in this country, we must mean everyone.

That must include women.

Now, I know there’s a myth in this country about Muslim women.

The idea that somehow all Muslim women are subservient observers of, rather than active participants in, British society.

Many are well educated and many play a vital role at the heart of their communities.

But we must not be naïve.

In certain sections of the community women are being denied access to education, work, and involvement in the political process.

These are all vital aspects of being a British citizen.

I’m told time and time again by women that the denial of these opportunities is not because of their Islamic faith but because of current cultural interpretations in Britain.

We must therefore be bold, and not hide behind the screen of cultural sensitivity…

…to say publicly that no woman should be denied rights which their country support, and, as we have learned from some speaker over the past couple of days, that some interpretations of Islam support too.

Empowering State

So bolstering our sense of identity and extending it to everyone is the first thing we need to do if we are to inspire people to feel British.

The second thing we have to do is build a society in which people really – and I mean really – have the power to shape their destinies.

These two things are mutually re-enforcing.

After all, common values, common identity and a common purpose can never be derived from the state alone.

They come from within society.

It’s a question of social responsibility: the attitudes, decisions and daily actions of every single person and every single organisation in society.

After all, it will be the many millions of individual acts between human beings that will determine the success of community cohesion.

And more people will assume their social responsibility and feel part of their community if they feel real control over its future.

Look at the Gallup World Poll.

It showed that what they dub as ‘involved’ citizens – that is, people who have donated money or volunteered time to an organisation, helped a stranger or voiced an opinion to a public official – are much more likely to think that people from minority ethnic groups enrich cultural life in Britain than those that are not involved.

The problem in Britain today is that the avenues and channels by which people are able to take control of their life and shape their own destiny have been eroded.

This is not just the case for minority ethnic populations. It is as true for the majority population too.

Britain is now one of the most centralised states in the developed world. People no longer feel they have the means or ability to change things.

When it comes to our schools, our health service, our neighbourhoods, people feel powerless to do anything.

Again, America can teach us a lesson.

It is one of the most decentralised countries in the world.

As a result, there exists a real sense of civic responsibility and engagement, as people look to their own community, not to central government, for solutions to the problems they face.

Just as importantly, they have a belief that no matter who they are or where they come from, if they work hard enough they can achieve their goals.

Afshin Ellian, an Iranian teaching Law in the Dutch town of Leiden, summed up the difference between this approach, and the one exercised in Europe:

“Five years ago, my Afghan sister-in-law emigrated to the United States, where she now works, pays taxes and takes part in public life. If she had turned up in Europe, she would still be undergoing treatment for her trauma – and she still wouldn’t have got a job or won acceptance as a citizen”.

What he is saying is obvious enough: a society that gives people the chance to get on in life, to fulfil their ambitions and feel that their contribution is part of a national effort is one that will inspire affection and loyalty.

So before we can offer real hope of changing society, we have to change the way we think and do politics in this country.

We need a radical re-distribution of power in our society from the centre to the local, so we can empower people and build the responsible society we all want to see.

The power to shape their communities.

The power to shape their public services.

The power to shape their futures.

In short, more power to the people.

I want to give everyone in our country, particularly in our great cities where immigrant communities are most concentrated, much greater control over what happens in their lives, with meaningful local participation, engagement and civic responsibility.

I know what you’ll say: Muslim communities already have a sense of civic responsibility that puts the rest of us to shame…

…and so the onus should be on the host population to step up to the plate and assume their responsibilities, by actively getting involved and reaching out to minority ethnic communities.

I agree with both sentiments entirely.

But the onus also lies with Muslim community and faith leaders, many of which are here today and whose work is an inspiration, to actively lead the communities they represent in the direction of involvement with the wider local community.

By that I mean extending their sense of civic responsibility and social work beyond places of worship or local community centres to people from other faith groups and backgrounds.

So let me be clear: we will not build a cohesive society if people do not assume their responsibilities.

And people will not assume their responsibilities if they do not have the power to control their lives.

“Power to the people” is one of the most deeply held Conservative ideas and in the weeks ahead we will start to show how we plan to extend it.

I began by saying that through a steadfast faith in our values and because society wanted to stand together as one, Britain has managed to answer the question of how we live together before.

And I said I believe we can do so again today.

It will require us to strengthen our identity and make it inspiring to many more people than is the case at the moment.

And it will require us to build the sort of responsible society that will make people want to play their part and stand together.

I am optimistic about our chances of doing this, because deep down, I believe the majority of us want the same.

A Britain proud of its past, and confident in its future.

A Britain built on a strong cultural identity but with the freedom to allow communities to practice their traditions.

And a Britain where if you want to play your part, there’s a place for you.