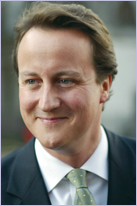

David Cameron – 2006 Speech on Disabled People

Below is the text of the speech made by David Cameron, the then Leader of the Opposition, at Capability Scotland on 16 October 2016.

First let me thank Capability Scotland for inviting me to speak here today.

The work you do – representing disabled people, advocating for them, providing care – is a great example of the idea that the modern Conservative Party stands for.

It is the big idea of the 21st century: social responsibility.

Social responsibility means understanding that the answers to the challenges we face do not lie in the hands of the state alone.

We must always ask not just what government can do, but what society can do – individuals, families, businesses, social enterprises and community organisations.

The borders of responsibility between state and society can never be neatly defined or set in stone.

For every issue, and every challenge, we must constantly ask ourselves whether we have got the balance right.

It is a fine judgement.

But we bring to this judgement a very different attitude to the one that the Government brings.

Where Labour instinctively reach for the regulatory solution, and trust first and foremost in state action…

…we instinctively reach for the human solution, and trust first and foremost in people and what they can do.

That is what social responsibility means, and over the next few weeks I want to explain its relevance to some of the biggest social challenges our country faces: an ageing population; giving hope and inspiration to young people, and the needs of carers.

DISABILITY

Today, I want to talk about our social responsibility to disabled people.

Earlier this year I announced a process of consultation with disabled people and disability organisations.

Jeremy Hunt, our shadow disability minister, has heard evidence from over 100 organisations.

That work goes on.

And today we are launching what I hope will become one of the main centres of discussion, advice and policy-making for disabled people.

It’s a website: www.thedisabilitychallenge.com.

I am so pleased that Bert Massie, the chair of the Disability Rights Commission, has said that we have “done a marvellous thing” in giving disabled people “a say in what a future Conservative Government would do.”

Well, this website is the way to have that say.

We want to hear from you about the issues that affect your lives – and how change can come about.

BBC AND PARKING

Because the great thing is that change really can come from the bottom-up.

Politicians can help, of course, providing leadership to a campaign and giving it greater profile.

But in the end, the most powerful force for change is society itself.

Let me give you two examples where Jeremy Hunt has shown the power of social pressure, not the law.

Working with the Royal National Institute for the Deaf, Jeremy has persuaded the BBC to double the amount of subtitling on BBC Parliament.

This means that people with limited hearing will be able to watch all major events in the House of Commons.

That is real change for the better.

And here’s another one.

Because of the unique parking pressures in central London, the four inner London boroughs are exempt from the Europe-wide Blue Badge parking scheme.

They operate their own parking arrangements for disabled drivers – which leads to real confusion.

Jeremy has brokered an arrangement which we can announce today.

For the first time, the four boroughs will work together to operate a harmonised disabled parking scheme and increase disabled parking.

SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AND DISABILITY

In the field of disability, the role of Government is to ensure that the benefits system helps, rather than hinders, disabled people looking for work.

Government is also there to fund and, where necessary, to provide the essential services that disabled people need.

But disabled people need more than Government benefits and Government services.

We need corporate responsibility too: businesses putting in the extra effort, even the extra investment…

…to ensure that they value and make proper use of the talents and abilities of disabled people.

We need civic responsibility: community groups and local government making sure that disabled people have the fullest access to local services and facilities…

…and independent organisations being trusted to provide services to disabled people.

And finally, we need personal responsibility.

This means each of us, as individuals.

Disabled people need to take the responsibility of looking for work if they can, of taking their place in society.

And non-disabled people need to combat their own prejudice and the prejudice of others – to recognise the equal rights of all people to respect and dignity.

THE SEVERELY DISABLED

That principle – the equal right of each of us to respect and dignity – must be the starting point of this discussion.

Every person – no matter their mental or physical condition – is of equal worth.

This is a moral absolute.

Humanity consists not in capability.

We do not derive our worth from our strength – physical or mental.

Our worth is innate in us.

Our humanity is intrinsic.

Indeed that word – humanity – is synonymous with the principle of compassion.

That is why the moral absolute of human equality is most tested, most necessary, when it comes to the most severely disabled people in our society.

As I shall explain, we must make every effort to ensure that disabled people can participate in the life of society – in the community, in work, in public life.

But the fact is, there is a small minority of people who will never be able to participate fully.

In our drive to include disabled people in normal life, we must not neglect those who will never live a normal life.

The other day I met a family who campaign for children on permanent ventilation.

The most important thing for those children is not access to every part of community life.

It is, quite simply, care: care for themselves and care for their families.

These are the most vulnerable people in our society – and they should therefore be the most cared-for, the most well-treated… quite simply the most important people in our society.

DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION ACT

But of course the vast majority of disabled people are fully able and willing to participate in work, in community life and public life.

It was my party which passed the Disability Discrimination Act in 1995, giving disabled people, for the first time, basic civil rights against discrimination.

It became illegal to refuse someone work, or a service, or an entitlement because of their disability.

I am proud of that.

But we have to go further.

Because equality means more than civil rights.

Fair treatment cannot come through law alone.

The first Race Relations Act was in 1965.

The first Sex Discrimination Act was in 1975.

Yet it took years for racism and sexism to start to disappear from public life – and as we know, they still haven’t disappeared altogether.

We don’t want to have to wait that long for disabled people.

Discrimination occurs as much in our culture as in our law – in society, as much as in the state.

That’s why we need to do more.

Our guiding principle should be to ensure that wherever possible, disabled people can participate in every aspect of life, and make their contribution to society.

SERVICES

I want to talk about work in a minute.

But there is more to life than work.

And even work depends on a host of other factors: childcare, housing, transport.

These things matter to all of us, but they matter even more for disabled people.

When the Conservative Party held a seminar on transport issues this summer, a disabled lady was late.

When she arrived, she explained that she’d sat on a train at Euston station for 35 minutes because no-one came to help her.

In the rush of modern life, it is easy for disabled people to get left behind.

The same goes for housing: in our rush to build, and to cram more people into smaller spaces, we can forget the needs of those who need special facilities at home.

According to the Government, nearly a quarter of disabled people who need adapted accommodation don’t have it.

That’s hardly surprising.

The Government’s Code for Sustainable Housing describes accessibility for disabled people as “an optional extra”.

As a survey for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation found, there is generally no single agency or department at the local level with responsibility for meeting the housing needs of disabled people.

Other services can neglect the needs of disabled people too.

Services like home help and occupational therapy.

Brilliant people do this work – but why is it so difficult to arrange a visit from them?

Why do they so often say they’ll come sometime between nine and five – meaning you have to stay in all day waiting for them?

How could someone hold down a job faced with that sort of inflexibility?

If supermarkets can give you an hour slot for when they deliver a box of groceries, why can’t social services manage it too?

A point I hear again and again is that people find it easier dealing with their disability than dealing with the agencies that are supposed to help them with it.

It’s often not the agencies’ fault.

Social services are often smothered in red tape.

In England, there’s the Commission for Social Care Inspection…

…Delivery and Improvement Standards…

…Performance Assessment Frameworks (of which there are 26)…

…Best Value Performance Indicators…

…they all take up time, require information, impose instructions.

Here in Scotland, social services are hampered by government in many ways.

A consultation by the Scottish Executive earlier this year found that social services are:

“overwhelmed by bureaucracy… often gathering information for local and national use which is of little value”.

It’s little wonder that there is such a shortage of social workers and care workers in many parts of Scotland.

WORK

Most disabled people don’t want to just be receivers of public services.

They want to be contributors too.

They want to work.

And the basic principle here must be that disability is not a disqualification.

The vast majority of disabled people are able, and willing, to work – whether full time or part time, paid or voluntary.

And yet 50 per cent of disabled people of working age are not in work.

The Government likes to boast that it has achieved near full employment.

And yet the fact is that millions of people of working age are not working – but they’re not categorised as unemployed either.

In order to help Government statistics, they’re simply written off.

There are around five million people who could work, who aren’t working.

Britain has the highest proportion of young men out of work in the developed world.

And according to the most recent Labour Force Survey, 40 per cent of all people of working age who are not working, are disabled.

MIGRANT WORKERS

So that’s one fact: five million people, many of them disabled, often able to work but who are not working.

And here is another fact, corresponding to the first one.

As we write off our fellow citizens from participating in the workforce, other countries’ citizens come to take their place.

The gaps in the labour market are, very naturally, being filled by migrant workers.

That, in itself, is a good thing not a bad thing.

We should not try to unlock the potential of our own citizens by locking out the citizens of other countries.

When willing, able and energetic people come to this country to work, they don’t crowd out other people from the labour market.

As the Fresh Talent initiative by the Scottish Executive recognises, skilled foreign workers expand our economy and make us more competitive.

Ultimately they create more employment.

But it is outrageous for Gordon Brown to claim that we nearly have full employment in this country.

Real unemployment in Britain is around five million – five million people left on the scrap-heap while British firms deal with the resulting labour shortage by employing migrant workers.

That is morally wrong and economically stupid and it has to stop.

We have a social responsibility to help disabled people into the workforce.

When millions of our fellow citizens are locked out of the workforce, we all lose.

They lose the quality of life – the wealth and fulfilment that comes from work.

Taxpayers lose because of the benefits that have to be paid to the unemployed.

And the economy loses because huge productive opportunities are wasted.

So our response to the numbers of disabled people who are not working is straightforward.

For the sake of the people who are locked into welfare…

…for the sake of taxpayers…

…and for the sake of our economy…

…we have to bring them back into the mainstream.

Into work.

WHY THEY DON’T WORK

So let us start by asking the obvious question: why is it that only 50 per cent of all disabled people of working age actually work?

Capability Scotland’s recent survey gives the answer.

Around half your respondents blamed discrimination by employers, who don’t want to hire disabled people.

And around half blamed the benefits system – trapping people in unemployment, because they don’t want to risk their benefits by getting a job.

I want to address these two issues in turn.

CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY

According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, nearly 40 per cent of employers are unwilling to consider job applications from disabled people.

And as the Disability Rights Commission reports today, the figure is even higher for people with a history of mental illness.

That is disgraceful.

And it’s unnecessary.

The fact is, most employers do the right thing when an existing employee becomes sick or disabled.

They make it work, both for the company and for the employee.

Yet too many businesses will not make this effort when it comes to recruiting new workers.

Some do, of course.

Companies like the Royal Mail have been far-sighted in their approach to the recruitment of disabled people.

This is the attitude we must expect from all employers.

It is simply a question of corporate responsibility – a key part of our wider social responsibility to disabled people.

CONSERVATIVE PARTY

That applies, of course, to political parties.

I am delighted that Jon Sparks, the chief executive of Scope, is here with us today.

He and I will sign an agreement this morning, between Scope and the Conservative Party…

…committing us to an employment policy which welcomes applications from disabled people.

Scope will conduct an audit of Conservative Campaign Head Quarters, and report back to us on how we can improve the way we work:

…access to our building, our literature, our websites.

They will also advise us on candidate selection.

I am sure they will find we are not perfect.

But I am determined that the Conservative Party becomes properly representative of the country we aspire to govern – and that includes more disabled candidates and more disabled MPs.

GOVERNMENT

Of course, there is one organisation which should be leading the way in corporate responsibility.

The largest employer in the country is the Government itself.

19% of the working age population is disabled – yet less than 5% of civil servants are disabled people.

At the Department of Work and Pensions – the department responsible for helping disabled people into work – only 7% of staff are disabled.

The DWP has actually lost discrimination tribunals brought against it by disabled staff.

All that needs to change.

We’re calling for an annual audit, across the public sector, of practice towards the employment of disabled people.

And if we win the next election, we will make the employment of disabled people a priority for recruitment policy throughout Whitehall and the public sector.

If we’re going to change attitudes in our country, government needs to set an example.

That is what social responsibility means.

BENEFITS: COMPLEXITY

So I want to see employers welcome disabled people.

The other side of our task, however, is to make disabled people welcome work.

As I’ve said, almost all do – in principle.

Almost all have something to contribute.

But the fact is that it’s often very difficult for a disabled person to make the transition into work.

The benefits system often hinders, rather than helps.

Most of all, because of its complexity.

The Disability Living Allowance.

Incapacity Benefit.

The Severe Disability Premium.

The Access to Work Fund.

The Individual Learning Fund.

The Wheelchair Service.

Funding from the local council for housing adaptations.

Funding from Social Services.

Funding from the LEA for Special Education Needs.

It goes on.

And on.

The Disability Living Allowance has a form that is forty pages long.

Half the appeals against DLA awards are upheld – which shows how many mistakes are made.

And you can tell how complicated the system is by this statistic:

26% of spending on families with severely disabled children goes on assessment and commissioning, not on care itself.

What a waste of money and of time.

Here’s another fact.

If you receive direct payments, you have to open a separate bank account for them.

The idea of direct payments is that people can be trusted to buy their own care.

Why do you need a separate bank account?

Direct payments are the right idea.

The problem is you can only get them if you only receive help from social services.

If you’re also getting help from the NHS, you can’t get your social care through direct payments.

I think that’s wrong.

In fact the idea that healthcare and social care should be kept in separate boxes is wrong.

It’s yet another confusion in a system which urgently needs to be simplified.

I’ve heard some real horror stories.

The family which had to wait three years to start getting Direct Payments when their disabled son turned 16 – including the threat of court.

The fact is, it is so difficult to navigate all this that when you’ve got the package you’re entitled to, you don’t want to change your circumstances again and risk it all.

Indeed, the system is so confusing that many people literally don’t understand where the money they receive comes from.

According to the Child Poverty Action Group, some families treat benefit payments as a windfall.

Because the system seems so arbitrary, because they cannot rely on a steady income from the benefits office, they simply spend it as it comes in.

BENEFITS: DISINCENTIVE TO WORK

And worst of all, people know that if they make the wrong move, their benefits can be withdrawn.

When I say “wrong move”, it’s actually often the right move.

People who suffer from a fluctuating condition – say Multiple Sclerosis or Bipolar Disorder – will often be able to work when they enjoy good health.

The problem is that if they suffer a relapse of the condition and have to give up work, they often have to start the whole benefits assessment process again.

So it’s no surprise that many people with fluctuating conditions think it is safer not to risk their vital benefit package by looking for work.

The system penalises responsibility in a variety of ways.

For example, surely it is a good thing if disabled people undertake part-time work, community work, education or training.

And yet all these things can trigger a new Personal Capacities Assessment, which can lead to a loss of “incapacity status” and therefore a loss of benefits.

Yet for many unemployed people these things are often crucial steps back to work.

You automatically lose your Incapacity Benefit if you work more than 16 hours a week or earn more than £80.

Again, this directly penalises part-time work, and encourages people to stay inactive.

BENEFITS: STATE AGENCIES

The same goes for the way contracts for Pathways to Work are awarded.

Contractors are rewarded for placing people in full-time employment – not for finding them part-time or voluntary work.

This acts as a disincentive to help the people in entrenched unemployment, the hard-to-reach groups with more severe disabilities who need help the most.

As Capability Scotland have put it, “Pathways to Work might not be the most appropriate vehicle for supporting people furthest from the labour market back into work.”

As for the New Deal for Disabled People, it doesn’t provide support before placing the client in work.

As a result, take-up is low and drop-out rates are high.

As Capability Scotland put it, “our experience suggests that NDDP might not be the most appropriate activity for people with complex support needs.”

Both the New Deal and Pathways to Work often seem to pick the easy targets.

The hardest cases have got more entrenched.

This is not the fault of the people who work in these agencies.

It is a structural problem.

When central government takes the responsibility for getting people into work, things tend to get bureaucratic and incentives get skewed.

SIMPLIFICATION

So there are the problems in the benefits system.

It is too complex.

It does not incentivise work sufficiently.

And it relies too much on large government agencies.

I believe we can tackle each of these problems.

Our policy review is examining the option of a radical simplification of the benefits package for disabled people.

I welcome the principle of Individual Budgets.

But I’d like to go much further.

Instead of the half-dozen different benefits a disabled person can receive – each with its different conditions and its own application form…

…we should be moving towards a single assessment process, and perhaps even a single benefit.

If it was not conditional on whether you work or not – it would not act as a disincentive to finding a job.

It would be simple, easy to administer and easy to understand.

WORK INCENTIVE

We also need to incentivise work directly.

And so Incapacity Benefit – the money that unemployed disabled people receive – also needs reform.

The committee stage of the Welfare Reform Bill starts tomorrow.

Jeremy Hunt will be leading our campaign to amend the Bill in favour of disabled people.

The Government has said it wants more severely disabled people to be able to volunteer for the Pathways programme.

If this is to be meaningful, we need to look at whether part-time work, voluntary work or community work could be considered valid outcomes for the programme.

For many people these can be vital stepping stones towards full time employment…

…but for others they may be the only realistic destination.

We also need to ensure that, if you have a prescribed medical condition that means you can manage frequent limited periods of work…

…you automatically go back to the same benefit entitlement every time you need to stop working.

And long-term, we need to think about how to overcome the abrupt cut-off for Incapacity Benefit at 16 hours or £80 a week….

…and the even lower earnings disregard for those on Income Support.

At every stage the benefit system needs to help, support and encourage people to take the next steps back into work.

That is the only way we will achieve the goal of independent living.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE

Finally, we need to put more trust in social enterprises and voluntary bodies.

As Capability Scotland has argued, Pathways to Work and the New Deal for Disabled People have not been effective with the people who most need help in getting into work.

Indeed I suspect that, like the rest of the New Deal, the successes have largely been with those people who would have found work anyway.

I do not believe that large state agencies, no matter how well-meaning, are the right vehicles for helping badly disadvantaged people into work.

Organisations like Forth Sector here in Edinburgh…

…or Unity Enterprise throughout Central Scotland…

…or the Shaw Trust across the UK…

…do great work getting disabled and mentally ill people into work.

I want to see far more use of social enterprises like these.

And not just for employment.

In every field of life, charities large and small are finding better ways of working.

Capability Scotland has two schools for disabled children – I congratulate you on their success.

I also want to pay tribute to a much smaller project – called Abbey Soft Play in Kelso.

When Diane Henderson’s daughter was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, she found there was nowhere safe for her to play in the town.

So Diane set up a social enterprise.

She converted an old disused toilet block into a soft play area for all the children of the town.

Now there are 250 members, about a third of them with special needs.

That’s a great example of how providing services for disabled people can help everyone.

There is a charity called Hurdles, in Bury in Lancashire, which helps disabled children…

“to be able to do what they wish, with whom they choose, at the same time as everyone else.”

That’s a brilliant description of what our ambition for disabled people should be.

And as Hurdles explained in a submission to our Social Justice Policy Group, organisations like theirs are generally better informed about what works than officials are.

They also told us, “often a small local organisation like Hurdles could deliver services at a fraction of the cost” that bigger agencies spend.

I want to see far more use of social enterprises like that – providing a gateway to government services, providing services directly themselves…

…and most of all, helping in all the messy ad hoc ways that human beings need help.

If we are to help the majority of disabled people achieve the goal of independent living…

…and if we are to help the minority that will never live independent lives…

…then we have to change the way we work.

All of us.

We as politicians have our job to do: Jeremy Hunt begins today on the detail of the Welfare Reform Bill.

But we as individuals, as employers, as citizens, have our roles too.

Personal responsibility.

Corporate responsibility.

Civic responsibility.

In a phrase: social responsibility.

That is the way to realise the moral absolute, the equal dignity of every person.