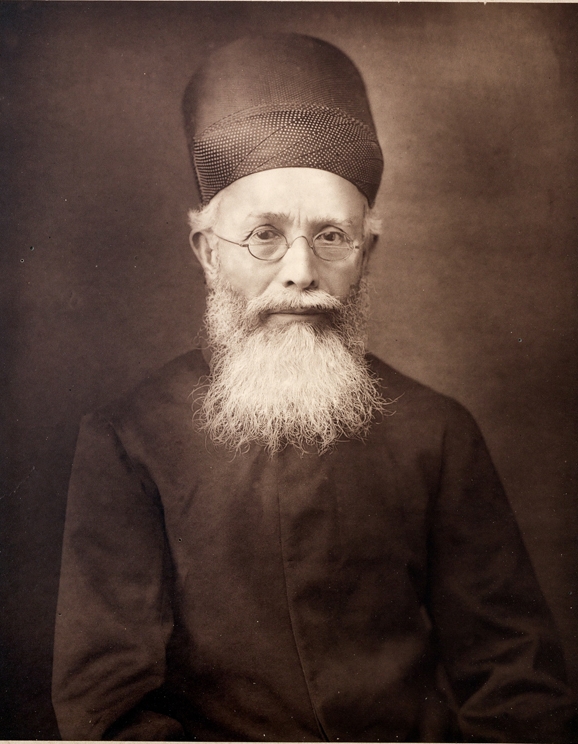

Below is the text of the speech made by Dadabhai Naoroji, the then Liberal MP for Finsbury Central, in the House of Commons on 8 August 1893.

I wish to offer a few observations. What was the first necessity from which this agitation began? That there ought to be a gold currency or a stoppage of coinage. There are two considerations, and India has one peculiar consideration, and that is that it has to remit to this country, whether rightly or wrongly, a certain sum of money yearly—namely, £19,000,000 in gold. Whatever you make of silver in India, as far as the people of India are concerned, they do not benefit in the slightest way in the remittances to this country, because they have to remit a certain quantity of produce, which ought to be able to provide £19,000,000 worth of gold in order to pay for the Home charges. Therefore, any effort made of changing or tampering with the currency, or any other plan devised, will have no effect whatever on the necessity of sending a certain quantity of produce according to the price of gold.

If gold rises in value, they (the Indian people) will have to send so much more produce; if it falls, they will have to send so much the less, be the proportion of silver what it may in India. In that respect the argument, and the principal argument, held out by the currency people and those who advocated the restriction of silver coinage—namely, that it would be a benefit to the people in India to restrict the coinage—is not borne out by the facts. Nothing of the kind will happen; the people of India will have to send a certain quantity of produce in accordance with the price of gold. So far, therefore, the unique political position of India, which has caused all this difficulty and the embarrassing of the Indian Government, is not in the slightest way improved by the plan the Government have adopted. The agitation began from the loss that the Europeans in India began to suffer for their remittances to this country. No such agitation arose between China and England, or any other country which had not to make any compulsory and political remittances in gold.

The original agitation in favour of the appreciation of silver began with the European servants, who desired to have some change in order that they should receive some higher exchange for their remittances than the value of silver allowed. Now, on that point the Government of India made up its mind. The Government of India wanted to give some higher or fixed exchange to the Indian officials for their own remittances only. Now, that was bad enough, and from this place I have complained of that. The Government of India have not paid the slightest consideration to the effect it would have on the people of India. But what is the result of the new arrangement? Here is a rupee artificially made worth 1s. 4d., whereas its real worth may be 1s., 1s. 1d., or 1s. 2d. The change, or whatever the difference will be, is not merely a gain to these Indian officials for that portion of their salaries which they have to remit to this country, but it is an advancement of their whole salary.

And not only all the Europeans, but all the native servants, have a higher value rupee paid for their salary in place of that which financially the price of silver would admit. The result is, therefore, that this would-be remedy is a pure loss to the unfortunate taxpayer of India, for he will have to find so many more valuable rupees in order to pay every servant so much more than his salary is. Suppose my salary is worth 100 rupees, I would receive 100 rupees, the artificial value of which will be 110 rupees. And this will apply to all salaries. In that way, therefore, there would be an extreme disadvantage, and the wretched taxpayer will have to find the difference. Next, suppose you take a man who has to pay an assessment of 10 rupees, and to pay those 10 rupees to the Government he has to sell part of his produce. Now, in order to pay the now 10 rupees, he will have to part with 10 to 16 per cent, more produce than he formerly did.

In every way, therefore, it is the taxpayer that has to suffer the loss arising from the mistake that the Government have made in adopting this policy. The Government is fortunate in one respect: that the injury that will be done through their plans has been, to a certain extent, modified by what is now happening in America, as many mines have been shut up. In America now there is also a chance of abolishing the Sherman Act, and the result of that will be, of course, a fall in the price of silver. But, on the other hand, if the repeal of the Sherman Act stops the American miners from working their mines, that will save India from the mischief. Our fate depends on the action of the United States. You may bring forth any quantity of abstract argument on one side or the other. The common sense of the matter is that the plan now adopted will simply be an addition to the burdens of the taxpayer; and unless it fortunately happens that the price of silver rises by reduction in its production the future of the Indian taxpayer will be certainly very terrible indeed. I want to say that the chief defect of this plan is that it was not necessary at all; that even from the Government point of view it was not necessary; but that as the plan is taken the whole effect of it is that the Indian taxpayer will have to suffer a great deal of loss in order to carry it out, unless he is saved by the rise in the price of silver.

There are many fallacies running about—we heard one from the right hon. Gentleman the Member for Sleaford (Mr. Chaplin)—to the effect that the balance of trade is in favour of India, and that fallacy has done more mischief and harm to India than any other thing. I cannot now enter into a discussion of it, but I hope to be able to show some time that nothing is further from the fact than to suppose there is a balance of trade in favour of India. I do not want to take up more time, but I want to sum up that the result of the present system will be that the burden of taxation upon the people of India will be very largely increased, unless the silver kings of the United States diminish their production of silver, and allow the price of silver to rise. But all these artificial methods adopted by Government for raising the price of silver will only complicate the currency; and that the Front Bench should be ready to defend a tampering with the currency in India is, to my mind, a very sad thing.

I will make just one remark with reference to the position of India in connection with the Front Bench. India under the Crown, in her relations with the Governments here, whether Conservative or Liberal, has, in one respect, been very unfortunate as compared with the time of the rule of the Company. When India was ruled by the Company the Company came before the House as before an independent tribunal. Now the Front Bench and the India Office are so much associated and identified that the Front Bench is put in the false position of defending the despotic, secret, and irresponsible India Office in everything they do. The result is, India is not able to get that redress and that independent judgment of an independent tribunal which she got in the time of the Company. This is made much worse by there being no periodical overhauling of the Indian Administration, and the mischief may go on increasing, till, perhaps, a day may come when it is too late to mend. It is of the utmost importance that the affairs of the India Office and the Government of India ought to be examined periodically; for this simple reason: that the House cannot follow the business or events of India from day to day.

The House must have special occasions to study and understand Indian affairs, pass judgment upon them, and introduce necessary reforms. Why should not the Front Bench, as an independent body, sit in judgment upon the India Office, instead of always sitting there in defence of the India Office, no matter whether right or wrong? It is a false position, and injurious to India. We believe that the Government have made a great mistake in interfering and tampering with the currency unnecessarily. We know gentlemen on the Front Bench are against such tampering with it; but they are put in a false position, and they have to defend the very thing they would otherwise not defend.

There is no reason whatever why the currency of India should be tampered with while the currency of England should not be tampered with. I hope some plan may be devised by which the Government in England may become an independent tribunal in reference to the conduct of the Government of India, and may hold the Indian Government in check, and control them instead of defending them in everything they do. The present system of Indian administration is in several respects very injurious to India, and whatever is injurious to India must and will be injurious to England.