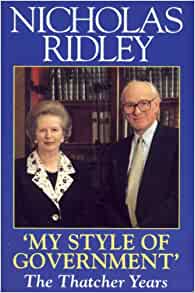

My Style of Government – The Thatcher Years by Nicholas Ridley

Nicholas Ridley (1929-1993) was one of the key Cabinet Minister supporters during Margaret Thatcher’s period of Government, serving as the Financial Secretary to the Treasury, the Secretary of State for Transport, the Secretary of State for the Environment and finally as the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry. This book was published in 1991 and it was the first insider’s account of the Thatcher years.

The book isn’t an autobiography by Ridley, although he briefly touches on what inspired him to become involved in politics and he cites the radical Government of Attlee in the immediate post-war period. Rather than being inspired by the ideas of Attlee it was the case that Ridley despised them, he was an early advocate for privatisation and he wanted the Government to be less involved in the lives of people. On nationalised industries he claims in the book that they are “dominated by their workforce, not their customers”.

Ridley initially liked the direction of the Heath Government in 1970, but then felt it lost its way quickly as events made the radical direction that Edward Heath desired much harder to deliver. He didn’t remain involved as when in 1972 Heath got in contact with Ridley regarding a sideways move in Government he said that he would rather return to the backbenches. Others such as Margaret Thatcher also had similar concerns about the direction of Heath’s Conservative Party, but she instead stayed inside the Cabinet as Education Secretary. When Heath lost in 1974, it was though Thatcher who reacted quickly to put her name forwards as soon as Keith Joseph ruled out standing for the leadership.

One element of the book is that it is very much ‘us against them’, whether that be the internal disputes between what Ridley refers to as the wets and the dries or between the two main parties. He writes that: “the Labour Party is bad at opposition. It is is basically lazy and goes home too early at night. Humour is virtually absent: their rhetoric is all righteous indignation and humour doesn’t fit with that. Tory oppositions are better at keeping the House late and mounting surprise attacks in the early hours”. There are these perhaps intellectually lazy sweeping assertions dotted around the book, but it is in general otherwise well written and readable.

The author deals with the issue of Thatcher’s preferred successors to her early on in the book, naming the three politicians who were at various times the heir apparent and having some sympathy with all of them. They were Cecil Parkinson, who was brought down more through scandal than political ability, John Moore who Ridley has more time for than some colleagues and finally John Major, who he says was “highly competent and very pleasant”.

On policy, Ridley refers a lot to his support for supply-economic measures and it’s evident that this was a point on which he had long firmly believed and he wasn’t a late convert on it. Margaret Thatcher in a speech in 1996 mentioned that Ridley could be argued to be more Thatcherite than her because of the length of time that Ridley had held his economic arguments. He was a firm supporter of privatisation, although makes claims about the deregulation of the bus industry that he was involved with, noting that his policies created large numbers of smaller independent bus companies and this was showing an increase in passenger usage. Unfortunately for Ridley, one of his proudest policies ultimately turned out very differently with passenger numbers almost relentlessly falling in the years and decades that followed.

Ridley continues on the policy theme with a defence of what he refers to as the poll tax, although formally called the Community Charge. Defending it is inevitable as he was one of the architects and designers of the policy, aimed to replace what he notes was the unfair rates system which needed radical modernisation. He remained someone who believed in the principles of the tax, but thought that it was essential to be brought in at a low level, which it ultimately wasn’t by his own admission. Ridley believed that the system would give voters a financial interest in keeping the tax levels set by local councils low. He makes nearly no criticism of Thatcher on the tax other by saying “she hadn’t taken the action necessary to ensure the new system’s acceptability by relating it more closely to ability to pay”.

The author makes clear that he supported a smaller state and lower taxes, but he didn’t want public services to be neglected. He cites figures that Margaret Thatcher over her period in Government increased real-terms spending on areas of health, social security and education by 37%, 35% and 16% respectively. This is part of his focus on defending against what opponents had said were the Thatcher cuts, noting that he felt she valued public services highly and that suggestions of the reverse aren’t backed by the economic evidence.

On the key issue of Europe, Ridley was a Euro-sceptic and firmly opposed to a single currency or monetary union. He was though a proponent of the Single Market and writes that Thatcher’s support “resulted in very great progress being made towards freeing the market of the Community”. Ridley was delighted with the Bruges speech made by Thatcher and how “it set out at length her concept of a Europe of nation states”. For anyone wanting to know what Thatcher would think of Brexit, there aren’t many clues as Ridley focuses nearly entirely on economic monetary union and doesn’t touch at all on the UK’s membership of the then European Community, simply noting how important the Single Market had been.

Ridley was devastated with the 1990 leadership election which led to Margaret Thatcher resigning as Prime Minister, but his criticisms are again mostly of other people. Although he notes Thatcher should have canvassed her MPs more as it proved she only needed to have changed the minds of a small number to have won the first ballot, much of the blame is laid at what Ridley refers to as “her weak campaign team”. This perhaps ignores the reality that if the Prime Minister had won by just one vote then it would have been politically challenging to have led what would be such a clearly split Conservative Party. This is a theme running through the book, nearly no criticism of Margaret Thatcher or at least only gently chiding, but plenty of time is spent finding scapegoats to explain why things did go wrong.

In his conclusion he notes that “I believe most of the supply side reforms will stick” and on this Ridley seems right as Tony Blair and Gordon Brown maintained and even built on some of the Thatcherite economic changes. Again Ridley mentions the work that Thatcher delivered on the Single Market, but he predicted that there would not be a European market open either internally or externally. He adds that “there was never a hint of corruption against her” and many in politics would agree that this was a period when the office of Prime Minister was taken very seriously by its occupants and in a way which might not have always been the case more recently. He ends the book writing that “the nation was oppressed by many dragons in 1979 and that Margaret Thatcher had come forth to slay them and the nation no longer had need of her”.

There’s never any doubt in the book that Ridley was one of the key supporters of Thatcher, but most readers of the book would perhaps be unlikely to have expected anything different. At the time of publication this was an important work because there was relatively little else available written by an insider, but since then there have been no shortage of books about the politics of the 1980s and also of course the auto-biography of Margaret Thatcher. Regardless of that, this remains an interesting book and it does make valiant efforts in explaining the logic behind policy decisions and it does touch a little on what went wrong.