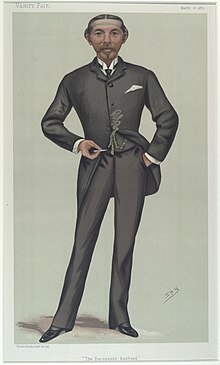

William Burdett-Coutts – 1921 Speech on Proportional Representation

The speech made by William Burdett-Coutts, the then Conservative MP for Abbey, in the House of Commons on 5 April 1921.

Looking back at the record of this House in relation to this proposal and at our experience of it during the last Parliament, I cannot but admit I am surprised at its being brought forward again so soon. I am not impressed by the long list of cases in which proportional representation has been adopted. The long list recited by my hon. Friend (Mr. A. Williams) seems to be impressive, and it mentions some places which no doubt have their own importance, but I wonder if the House has examined it, because if it has, it will have found that it deals with extremely contracted electorates, in many cases minute ones, in which the election is carried on under conditions which have no possible similarity to those involving a great Parliamentary institution. To my mind, we can well put them all on one side with one exception, and that is the one case in which in the British Empire proportional representation has been applied to a popular assembly under the Constitution. I will not deal with the case of Tasmania, which is the greatest mystery to both our side of this question and to my hon. Friend. We know nothing about the progress of the scheme there. All that can be said in the ninth circular issued by proportional representation supporters in the course of last month is, that Sir John McCall said, at some time or other, that proportional representation had “come to stay.” Sir John McCall is the gentleman who, years ago, applied proportional representation to Tasmania. We are not told the date at which he made this statement. I am under the impression that he is no longer in existence, but at some time or other he said “proportional representation has come to stay.” It has stayed, because the party which got in by proportional representation is extremely likely to try and preserve it. There is no evidence at all that proportional representation is acceptable to the people of Tasmania. Indeed—although one does not like to mention evidence from private sources—I have a good deal of information to exactly the contrary effect. Therefore I think we can put Tasmania on one side and come at once to the crucial instance quoted, and that is the case of New South Wales. I look upon that as the only fair test of the application of proportional representation to a great popular assembly. What has been the result there? In the first place, the hon. John Storey and his party are in power in New South Wales. How? By the majority, the magnificent majority by quotas, which you say you are going to get by proportional representation in this country? Not at all. He is in power on the strength of a minority of one in four of the whole electorate of New South Wales. Is that a system which you want introduced into this country? Moreover there are incidental peculiarities which have shown themselves clearly in New South Wales. The election in New South Wales is carried on upon lines which absolutely deprive the elector of all freedom and of all voluntary momentum in the matter. Can anything be imagined which is so destructive of the basis upon which we want to put elections—of the freedom and spontaneity, so to speak, of the electors? Can anything be more destructive to that than the system which pervades both parties in New South Wales, and which is rendered necessary by this complicated system of preferences—that is to say, the domination of the caucus of each party, who get the whole thing into their hands. They are the “half-dozen clever men” who, Mr. Massey said, could carry any election they liked under the preference system. These half-dozen clever men sit down to work, and the calculation of the number of these preferences, in order that they may get as many men as possible of their own party in, is a most elaborate and scientific process which no elector could possibly undertake for himself. When they have done this, they make out what is called their “How to Vote” Card, and that is given out to different batches of electors; and so necessary is this, so minute is the control of the caucus, and so essential is its operation to the exercise of what should be the free right of the electors, that no elector who wants his party to succeed dare go into the polling booth in New South Wales without one of these cards. That is the one specimen—

Lord HUGH CECIL No, it is not.

Mr. BURDETT-COUTTS Of the application of proportional representation. The Noble Lord will have plenty of opportunity—

Lord H. CECIL I am entitled to contradict a misstatement.

Mr. BURDETT-COUTTS I am aware that the House of Commons likes a conversational style of speaking, but I am not sure that it likes Debate carried on by conversation. That is the one specimen, applied to English-speaking people within the ambit of British parliamentary institutions, which we can call into evidence on this occasion. I began to speak on the record of this House in relation to this subject, and I should like to remind the House of one feature in the case, which has been referred to by previous speakers, namely, the rejection of what was called minority representation in 1885. As has been mentioned, and as, I daresay, most hon. Members know, minority representation was introduced in Mr. Disraeli’s Reform Bill of 1867. It created the Birmingham Caucus under Mr. Schnadhorst. It held Birmingham for 17 years like a vice on the side of one party. It became detested by the electors, and, when it came before this House 17 years afterwards, in 1885, it had scarcely a voice in its favour. I think it only got 31 votes, and the House decided against it.

There was one feature in that episode which I think it is worth while to recall. That House turned down minority representation—and minority representation, whatever the difference in technique between that plan and this, is the whole principle and the main object of proportional representation—because it was in touch with the practical experiment that had been made in this country. It had been able to watch what had been going on in these great cities where minority representation was in practice during that period of 17 years, and the results were such, and the effect upon the electors was such, that the House of Commons decided to abolish it altogether. And in so doing that House of Commons had in its memory, and could recall and vindicate, the advice of giant statesmen in this country, who, when it was first introduced in 1867, had denounced it in unmeasured terms, and had pointed out the results that would ensue from it. I wonder if I might recall to hon. Members a quotation which, although, perhaps, familiar to many of them, may not be within the knowledge of all: He had always been of opinion that this and other schemes, having for their object to represent minorities, were admirable schemes for bringing crochety men into the House. They were the schemes of coteries and not the politics of nations, and, if adopted, would end in discomfiture and confusion. There was another—these statesmen were on both sides. That was Mr. Disraeli.

Mr. J. JONES A friend of Germany.

Mr. BURDETT-COUTTS Now we will come to the other side—to Mr. John Bright. Was he a friend of Germany?

Mr. JONES A friend of every country.

Mr. BURDETT-COUTTS Mr. John Bright said: Every Englishman ought to know that anything which enfeebles the representative powers and lessens the vitality of the electoral system, which puts in the nominees of little cliques, here representing a majority and there a minority, but having no real influence among the people—every system like that weakens and must ultimately destroy the power and the force of your Executive Government.… A principle could hardly be devised more calculated to destroy the vitality of the elective system, and to produce stagnation, not only of the most complete, but of the most fatal character, affecting public affairs. Mr. Gladstone, Mr. Goschen, and others were not less emphatic.

With regard to the last House, I need not remind hon. Members that the last House of Commons had many opportunities of exhaustively discussing this question—not merely the opportunity of a Friday afternoon. It was debated over and over again, and it was defeated in the House by majorities always increasing until they became overwhelming. As this present House may not like to be compared to the former House, or any other House, may I ask whether it remembers that that House cannot be said to have been opposed to change? It carried the greatest extension of the franchise known in this country for nearly 100 years, and it carried the greatest revolution in the franchise conceivable—female suffrage. When, however, it came to this proposal, after exhaustive debate, after its being tried and placed before the House in every possible form, the House turned it down decisively on every occasion. I shall have something to say about this Bill and what it contains, and one of the points to which I desire to call attention is that the Bill is compulsory. That was not the case in 1918. After the final defeat of that measure in the House of Commons, the Upper Chamber insisted upon proportional representation being introduced into the Bill, but it took the form of a commission of inquiry to go round the country and to inquire into the opinion of the electors. We who were in that House remember that the result of the inquiry held in 149 constituencies for the purpose of selecting 100 constituencies for proportional representation was a great preponderance of opinion on the part of the electorate against the scheme. Then it came back to this House, and this House gave it the coup de grâce.

Before dealing with the Bill we are now discussing, I should like to say a word as to the spirit in which I approach this subject, vis-à-vis of hon. Members who support the Bill. I ought to have said it at the opening of my remarks, because I do not wish to be misunderstood. I am the last person to question the sincerity of their feelings, and the strength of their convictions that the change they propose will improve our Parliamentary representation, and will do away with apparent anomalies which press heavily on minds like that of my Noble Friend (Lord H. Cecil), which are animated and directed by what are called counsels of perfection. Indeed, in that respect I admire them. I even envy them. They live far above this earth, in an atmosphere filled with ideals, theories, postulates, and promises of electoral millenniums, which every now and then they hand down to us ordinary mortals on the earth like a sort of manna which, much to their amazement, for 50 years we carnal people have found peculiarly indigestible, and which only minorities can be induced to accept and to swallow without knowing what it will do to them, and I fancy with a very uneasy suspicion that if they ever become majorities it will do them no good. I hope I am not impolite to my hon. Friends in the figure of speech I have used. If I were to go for guidance in such a matter to the greatest model of oratory that ever addressed this House, I should find that Mr. John Bright spoke of the minority representation Clause in the Bill he was discussing as “an odious and infamous Clause, which ought to have come from Bedlam, or some region like that.” I would not say a thing of that sort. I have spoken only of the higher and not the nether atmosphere in which the academics live, generally presided over, I believe, by the Minister of Education, and now and then indulging in the innocent amusement of toy model elections and the even more harmless one of throwing down to the House of Commons—I mean from above—some manifesto saying, with needless verbiage, that some statement of mine “has no foundation in fact.”

But as I myself have to live on hard ground, and cannot find any amusement in a subject like proportional representation, except possibly its name, I should like to go at once to the Bill and offer a few remarks upon it. The hon. Member who moved it said he wanted to let the light of day in upon the Bill. I will endeavour to do so by taking, in the first place, what the Bill does, and then what it does not do. The first thing it does is to commit this House for the first time, and, I suppose, once and for all, to proportional representation, with the single transferable vote and its system of first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh preferences—a system so strange and complicated that I hope the House will forgive me if I say I do not believe there is one in 20 Members who understands its working, and so far removed from commonsense and practical utility that the remaining 19 have turned away from the task of trying to understand it. And also a system, the, results of which in any particular election are rendered uncertain and almost staggering to the electors by reason of the very large part played in them by the element of chance. The hon. Gentleman who moved the rejection gave one or two very striking cases of the amazing results derived from it.

Secondly, and I make more of this, this is a compulsory Bill. The promoters hitherto, I recognise, have always been on the horns of dilemma. They must either make the Bill optional, which would represent a partial proportional representation and turn the country into a patchwork of different systems, or they must make it compulsory. They have done the latter. They have made it compulsory, as I understand it, with very few exceptions over the whole country. I want to ask the House to consider what it is we are dealing with. We are dealing with the most highly valued function that citizenship in a self-governing country possesses. The method of performing that function is intimately connected with the elector himself. It is something that is the property of the electorate, and we are dealing with that in a way which, whether it be good or whether it be bad, is a way on which we have never in any form consulted the electors of this country, except on one occasion. For this House radically to change the method of the electors exercising that great function, and to change it ex-cathedrâ without in any way or form consulting the great electorate of the country, is straining the representative character of the House of Commons. The electors have never given any opinion upon this subject, except on a single occasion, and that is an occasion which strengthens my argument. It was the occasion to which I have referred when a Royal Commission, insisted upon by the House of Lords, went round the country and tried to gather the local opinion of the electors. I pay this tribute to the House of Lords that whereas they did not go beyond their constitutional right but, in my opinion, went beyond their moral claim as a non-elective Chamber in insisting upon proportional representation being placed in a Bill dealing with a matter which is really the function of the elective branch of the Constitution, yet they did it in a form which consulted the people. It is a tribute to the fairness of that House that they did it in the form of a Commission of Inquiry all over the country, and the result of that Commission was to turn the whole proposal down.

Now we are asked to take another course. We are asked to take a course which I consider arbitrary and illegitimate—that is, to force upon the electors of this country, without their being consulted, without their being in the least familiar with this process of proportional representation, or knowing anything about it, a new system which will throw them into confusion and which, if we look at its results in New South Wales, will turn them away from and make them dislike and distrust the polling booth as an instrument of representative government. I do not think I am exaggerating when I put it so high as this, with regard to the electorate, that there are few Members in this House who could go down to their constituencies and really explain the working of the system which is to be forced upon them. Have we any right in this House to pass such a Bill without putting the question to the usual test? Other questions involving great principles and revolutionary changes are always put to the country by being explained election after election on the platform, and even if you do not get a direct vote you get an indication of popular opinion in regard to them. I have no desire to limit the constitutional powers of Parliament with regard to its legislative or administrative functions; but I respectfully submit that, in the absence of any such normal process of consultation with the people, for this House to force this revolution in the use of the vote upon them is an abuse of its moral right.

There is a third thing that the Bill does. It fixes arbitrarily the size of the constituencies to which proportional representation is to be applied. There are three-, four-, five-, six-, and seven-Member constituencies. I should like to comment as briefly as I can on the two ends of this structure. It has been shown in various pamphlets and documents, that in the three-Member constituency proportional representation will have exactly the same result as the minority representation of 1867. Therefore, it is a bad thing, because the results of that were so bad that it was turned down by the House of Commons after 17 years’ experience. With regard to a seven-Member constituency, why do the supporters of this Bill stop at that size? Have they forgotten that Lord Courtney, the great protagonist of proportional representation, was always of opinion, and stated it over and over again, that the larger the constituency the more effective and just would be the application of proportional representation. He defined a 15-Member constituency as the right size. Why have my hon. Friends forgotten the teachings of their great leader on this question? Simply because a 15-Member constituency would be rather too startling for the House. Therefore, they have sacrificed what is the fundamental principle of proportional representation for the sake of appearances.

In this connection I must turn to what may be a novel point, but one that will be clear to those who look into this question. You cannot have true proportional representation without eliminating the constituencies altogether, and turning the whole country into one constituency. All the figures that have been given for years after a General Election about such and such a number of votes in the country which have been given in support of Labour, or in support of Independent Liberals, or in support of the Coalition not being proportionately represented by the seats they have gained in Parliament rest on a rotten basis, so far as any remedy promised by this scheme is concerned. It is an utterly fallacious argument. May I make the thing clear to the House by a concrete example? Supposing you take what we may call a sectional issue. We will say that it is local option or anti-vivisection. Things of that sort come up at elections and influence the electors. There are people who feel very strongly about them, and who consider them as the first subject to which Parliament ought to attend. Take the question of local option. There might be sufficient local optionists in one or two constituencies to return their candidate to Parliament, but what about the local optionists all over the country, living in other constituencies, and having votes in those constituencies, but not in sufficient numbers to enable them to get a local option representative for their constituency? How can you gather those together and give them seats in this House in proportion to their numbers without sweeping away constituencies altogether? I hope I have made the thing clear. That is why Lord Courtney said that a 15-Member constituency was the best, because he saw that he would get somewhat nearer to the ideal and a little nearer to the actual function of proportional representation by means of the 15-Member constituency. The postulate with which I started this explanation, that you cannot have true satisfactory logical proportional representation unless you turn the whole of England into one constituency, connects itself with a curious personal experience which I will venture to mention. I studied the whole subject of proportional representation carefully after my attention was first drawn to it and I came to this conclusion. But it was so surprising that I did not bring it forward. Then, one day, I came across a very remarkable vindication of it. It was this, that Thomas Hare, who invented proportional representation and the single transferable vote in the early fifties of last century, invented it with the express purpose of turning the whole of England into one constituency.

I have no time to enumerate the many things that this Bill does not do. Nor is that necessary, because it trots out the old device of a Royal Commission. It takes out of the hands of Parliament innumerable subjects that it is qualified to deal with and is responsible for dealing with, and places them in the hands of a body of which we know nothing. It is true that the Commission has to report to this House. After that everything is to be done by Orders in Council. I speak with a long memory of this House, and I submit that this kind of legislation by a combination of Royal Commissions and Orders in Council is the very worst sort of legislation we could have.

There is one question which I would ask my Noble Friend the Member for Hitchin (Lord R. Cecil). I have spoken over and over again of government by groups. I feel strongly on that point. Under proportional representation we shall simply have a repetition of what we see abroad—a change of ministry every six months and no stability of policy. This is a subject on which we want clear thinking. What is to be the position of groups or sections of opinion which it is hoped to get into this House? Is it party or non-party on which they base themselves? In other words, is it the argument or expectation that under their system adherents of sectional opinion, whether in groups or as individuals, should stand for Parliament under the aegis or protection of a political party or should stand on their own? That is an important question to which I should like to have an answer. We had it definitely from Mr. Holman, who was so long Premier of New South Wales, that sectional representatives have “no hope of getting in where one of the machines did not offer some sheltering niche as a refuge.” There is nothing to tell us definitely whether the supporters of proportional representation are of the same opinion. They say in one case that the candidates are “as free as air” and in another that representation of all shades of opinion and of different classes is to be got within each of the two parties. Then there is a subordinate question of some importance, whether these sectional candidates, representing sectional opinions, pledge themselves to their supporters to put their special policy forward and to give it the first position in their parliamentary career? If they get into a Parliament under the ægis of a party do they pledge themselves to force that on the party? That is an important question, but I do not think that it really affects the alternatives. The two alternatives are those which I have put.

If these sectional groups go in under the ægis of a, political party, which will mean going in by the aid of its machine, they will have to put party first and become members of that party. But that is exactly the position in Parliament now, and there is no reason to change our whole electoral system to secure it. Every party is formed of groups, and these groups pursue the reasonable, legitimate, practical course of trying to infuse their opinions into the mass of the party and impress their policy on their leaders. But they do not, when it comes to a critical Division, threaten the leaders of their own party to go on the other side if they do not get their own way for their sectional policy. Prom all the pronouncements that I have read, which have been issued by the Proportional Representation Society, I gather that the vision that is held out to the political life of the country is that proportional representation will return representatives of minorities, independent; that it will return individuals, independent; and that anyone can get into Parliament, on his own, if he has sufficient support. If that is the case, the result undoubtedly would be government by groups, because you will have these groups of opinion not bound to either party, and Members can go to one party or another on the eve of a critical Division and say: “Give us our policy and we will vote for you, but if you do not give it to us we will throw you out.” That position would be most dangerous to the dignity and stability of Parliament. I earnestly urge the House, for reasons of the welfare of the State and the freedom of the elector, to throw out the Bill.